- As Plastic-Free July comes to an end, we analysed the media debate around the global movement to see what we can learn from a PR and comms perspective.

- We found that Plastic-Free July is still not a massive initiative and brands should take part by focusing on calls-to-action messaging rather than promoting sustainability credentials.

- In addition, brands should try to own the narrative around their efforts to stop pollution and curb fear messaging while concentrating on effectiveness.

Established in Australia in 2011, Plastic-Free July has spread to more than 190 countries, with over 140 dedicated to the challenge.

The theme of this year’s initiative, “Turn the Tide, one choice at a time”, celebrates the collective impact of millions across the world choosing to refuse plastics, from governments and brands to individuals.

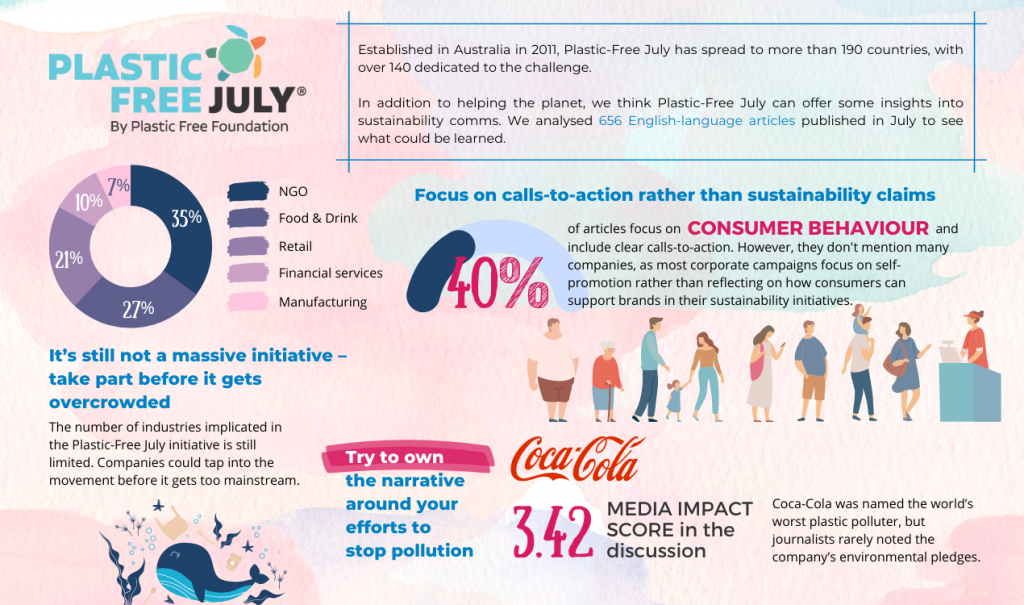

In addition to helping the planet, we think Plastic-Free July can offer some insights into sustainability comms. We analysed 656 English-language articles published in July to see what could be learned. Here are our main takeaways:

1. It’s still not a massive initiative – take part before it gets overcrowded

Our analysis showed that the number of industries implicated in the Plastic-Free July initiative is still limited:

Naturally, NGOs dominated the debate as they shared research findings and put pressure on companies to reduce their plastic footprint. The Food and Drink, Retail, Financial Services and Manufacturing industries all featured as they engaged with Plastic-Free July, often in response to being blamed for polluting.

However, some industries that are regularly scrutinised in the media still haven’t taken part in Plastic-Free July, which goes to show that there’s an opportunity to be seized – companies could tap into the movement before it gets too overcrowded.

For example, fashion brands could capitalise on the initiative, since fashion, particularly fast fashion, is regularly blamed for being a major contributor to plastic pollution in the form of microplastic fibres. The pharma industry, which is also accused for contributing to global GHG emissions with its plastic packaging, could also add Plastic-Free July to its ESG campaigns.

2. Focus on calls-to-action rather than sustainability claims

We found that the largest topic in the debate was Consumer behaviour, as most articles focused on how individuals could reduce their plastic consumption. Typical headlines included: “20 ways to reduce plastic in your life”, “Go plastic-free this July” and “Here’s How You Can Participate in Plastic Free July”.

The popularity of these “call-to-action” articles brings an important lesson to PR and comms professionals. Most corporate sustainability campaigns revolve around claims of going “100% recyclable”, being “100% recycled”, having “30% less plastic”, being “100% natural” – and so on. But when the tonality of communication is in the form of “claims” rather than a “call-to-action”, it invariably takes the pressure off consumers, and even makes them unsure of how to respond.

While “100% recyclable” claims are appreciable, consumers often don’t understand how they are expected to respond to these. In the absence of a clear call-to-action for consumers, the responses most often are, “Ok, great, so what?”. Alternatively, consumers see such claims as an opportunity to push businesses further by upping their expectations from the business, e.g. “Shouldn’t they have already been 100% recyclable by now?”, rather than reflecting on how they can support the business in their sustainability initiatives.

Persuading people to change how and what they buy to support a sustainable future is both difficult and complex. However, by segmenting messaging to span the divide between adopters and sceptics, telling positive and empowering stories fixed in the present, and finding creative ways to overhaul the often clichéd visual language of sustainability, marketers can usher in long-lasting, cross-generational and cross-cultural change. Persuasion is key in any form of marketing, but in green comms it must be approached with real caution and nuance.

3. Try to own the narrative around your efforts to stop pollution

Our analysis also showed that the most influential companies in the Plastic-Free July debate were implicated in new research findings blaming them for contributing to plastic pollution.

We determine an organisation’s media impact in the context of a topic by looking at its media influence score calculated in terms of coverage by high-profile media outlets, topic relevancy score measuring its contextual relevance, and media visibility as measured by the number of mentions.

The most influential organisation is the Plastic Free Foundation, which organises Plastic-Free July, followed by Greenpeace, which released new plastic research and called on the governments to ban single-use plastic bottles.

Most companies in our sample, such as Coca-Cola, Starbucks and Costa Coffee, were featured in the discussion for being accused of contributing to plastic pollution. Even banks such as Barclays and HSBC were referenced for providing finance to single-use plastic producers and to the plastic packaging industry.

And even though all these companies have sustainability initiatives in place, few media outlets mentioned them. For example, Coca-Cola was named the world’s worst plastic polluter numerous times, but journalists rarely noted the company’s pledges to make 100% of its packaging recyclable globally by 2025 and to use at least 50% recycled material in its packaging by 2030.

Sustainability initiatives can go unnoticed by the media simply out of flawed communication. Labelling anything and everything you do as “recyclable”, “made with recycled material” or “green” can backfire if you don’t back up these claims with real attributes and outcomes. Today, these terms are used so often that people hardly notice them – and may consider them shallow, meaningless words unless you are able to explain exactly why your product has a reduced impact or how much CO2 it avoids.

Companies should try replacing catchphrases or slogans with some simple but measurable details, supported by facts and data: your audience will come away with a better understanding of your efforts, and you will have planted a seed of trust in them. An environmental claim must be transparent and properly defined. Vague or general terms with multiple meanings should be clearly explained.

4. The time for pledges is over – demonstrate some action!

Following our previous point, companies should do more than pledge to gain positive media coverage with initiatives like Plastic-Free July. Facing a reckoning over their contribution to the environmental crisis, companies are coming out with a record number of pledges. At least a fifth of the world’s 2,000 largest public companies have now made some kind of “net zero” pledge to cancel out their carbon emissions.

But environmental action pledges are no longer sufficient, and corporations are losing the ability to “fudge the numbers” on sustainability policies. Business must show, not tell. Moving forward, the focus will be on clear, understandable pathways and actionable execution of plastic-free or recycling strategies.

Most consumers want companies to stand up for the issues they are passionate about. However, corporate and brand activism needs to go beyond a short-term campaign and permeate all aspects of the company’s activities in the long term. Brands should take care that any cause they embrace is an authentic fit and should be sincere, transparent and outspoken about what they are doing and why.

While activism is an opportunity to create emotional connections with consumers, brands need to avoid stirring up too much emotion and guilt in communications to ensure that it resonates.

5. Curb fear messaging and concentrate on effectiveness on both traditional and social media

Environmental communicators have long pointed to the excessive use of fear messaging around sustainability as one of the main problems with engaging the public on this subject.

The challenge is to pair fear messaging with information about efficacy, namely what people can actually do to mitigate the fear. The combination of fear and efficacy leads to what is known as “danger control,” actions to mitigate the danger, as opposed to “fear control,” actions to shut down the fear.

In the case of COVID-19, the sense of efficacy was clear: hand washing, social distancing, masking. With sustainability, efficacy information is far less obvious and more difficult to act upon.

Take for instance the most effective communicator in the Plastic-Free July debate, Rebecca Prince–Ruiz, Founder and Executive Director of Plastic Free Foundation.

Rebecca Prince-Ruiz’s messaging was all about efficacy: she remarked how the initiative helped avoid 2.1 million tonnes of plastic waste, including millions of single-use drink bottles, coffee cups, packaging, straws and plastic bags. She added that every choice we make in our own lives to reduce our plastic waste makes a difference, it sends a message and helps builds momentum – turning the tide on plastic pollution.

Such messaging focused on efficacy can be more than just traditional media statements – it can be as simple as posting photos to social media from community cleanup drives, nature walks or posts about any kind of pro-environmental behaviour, such as taking transit.

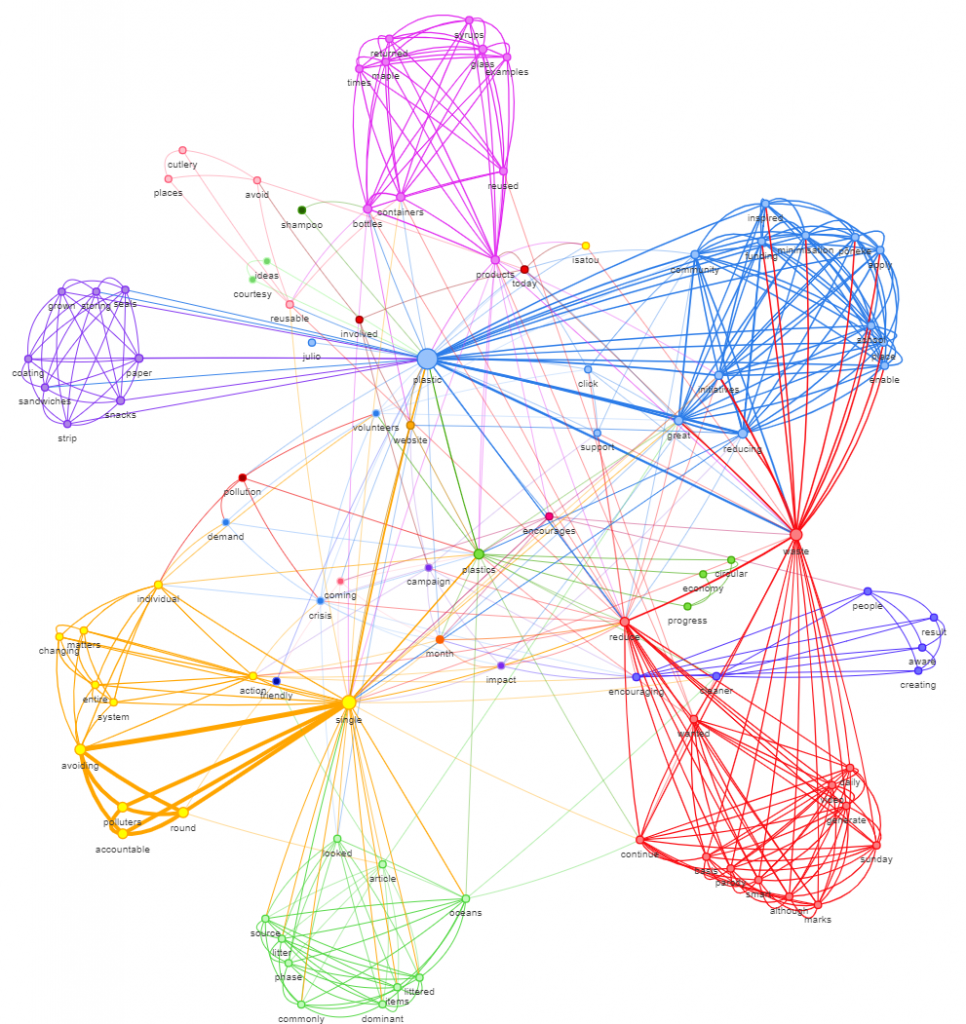

In fact, consumers regularly use social media to share practical information on how to handle plastic pollution, as evidenced by our analysis of 250 tweets from the last week of Plastic-Free July.

As we can see from this keyword network graph of the discussion, a large portion of the discussion revolved around “bottles”, “syrups”, “containers”, “cutlery”, “shampoo” and other objects that users referenced in their efforts to deal with plastic waste.

Stories about effectiveness, even as simple as sharing how someone recycled their plastic bottles, can send a message that action to help the environment by ordinary people is doable, normal, empowering and desirable. They energise and mobilise members of the public ready to take action, by providing visual examples of who is leading the way.

They also move the conversation beyond the conventional emphasis on sceptics and deniers and normalise pro-environmental values and behaviours for the growing number of people who are already alarmed or concerned about the environment. Far from driving the fear narrative, stories of sustainability solutions unlock people’s sense of efficacy and agency in the face of impending danger.