The media can have a disproportionate impact on your company’s reputation, leading many to speak of ‘media reputation’, or the overall evaluation of an organization as presented in the media.

Far be it from me to equate media coverage with corporate reputation, it may be argued that for companies in the pharmaceutical industry, how stakeholders perceive them is influenced primarily by the lay traditional, online and social media. Thus, media coverage is an important input into stakeholders’ perceptions of a pharma company, which effectively constitutes its reputation.

Managing reputation in the pharmaceutical industry, therefore, requires a strategic approach to corporate communications and media relations, which takes into account the changing context of media consumption and the recent trends in healthcare communications.

Media Context and the Echo Chamber Effect

More than ever when managing media relations, PR practitioners in pharma and healthcare need to understand who reads the news, who is influenced by those news, and what’s the level of trust people have towards what they read or hear from the media. The reason for this is the declining trust in media overall, as indicated by the 2017 Edelman Trust Barometer. The annual trust and credibility survey emphasizes that trust in the four institutions of government, business, media, and NGOs continues to decline, with media declining the most.

We would make the wrong conclusions, though, if we look at the media collectively, without recognizing the different context every media organization is set in, as evidenced by the fact that people who consume news from online-only media are not consuming legacy media brands, so in many ways it is a different constituency and a different market. A proof of that can be found when we look at the Edelman Trust Barometer per media type:

Figure 1: Percentage trust in each source for general news in 2017 vs 2012

Source: 2017 Edelman Trust Barometer

While trust in traditional media falls, the credibility of online sources rises. In this regard, the survey’s findings corroborate prior research published in the American Behavioral Scientist in 2010 that has found exposure to online media to correlate with distrust of mainstream media.

In the context of pharma, where communications professionals’ efforts have traditionally been focused on mainstream media press relations and tracking press release penetration, the majority of the general population is reported to find leaked information more believable than press statements. Such leaked information is increasingly finding its place in alternative media outlets, which have challenged the traditional authority of journalists, both directly and indirectly, and have in many ways catalyzed widespread attention to the problem of fake news.

In some countries such as the USA, the world’s most important national market for pharma, PR professionals have to deal with an ever-growing politically-based polarization in news selection. In this regard, political partisans, particularly conservatives, consider traditional or mainstream media as liberally biased against their worldviews.

The rising trust in online-only media, both mainstream and alternative, have led millions of people to tune more deeply into the news sources they trust and tune out all others, creating the so-called ‘Echo Chamber Effect’. Related to that is another media effect, consistently identified in annual surveys as ‘the Fox Effect’, which states that watching Fox News renders people less knowledgeable about public affairs than if they had watched no news at all.

For example, with regards to healthcare, research published in the Social Science Quarterly has demonstrated that Fox viewers consistently report more erroneous knowledge than viewers of other news outlets on what is contained in the Affordable Care Act, otherwise known as Obamacare.

The Branding-Reputation Dilemma

It is rare to hear the word ‘brand’ used when speaking about prescription drugs. They are mostly called ‘products’, and it may be argued that a true global pharma brand is difficult to create because of the differing local conditions, cultures, and languages across countries, as well as local subsidiary structures.

Recently there has been a general move towards corporate branding in many industries, a shift that benefits pharmaceutical companies in their attempts to link the name of the brand and the company in order to capitalize on those positive attributes held by stakeholders and the general public about the firm.

Nevertheless, more often than not, it is a pharmaceutical company’s reputation, not its corporate brand, that comes into the limelight. Likewise, it is not uncommon to think that brand and reputation are synonymous. To differentiate between the two, I will refer to reputation gurus Charles Fombrun and Cees B.M. Van Riel, who define ‘reputation’ in their famous book “Fame and Fortune: How Successful Companies Build Winning Reputations” as the assessments of multiple stakeholders about a company’s ability to fulfil their expectations, fueled by a brand’s promise.

It follows that a company may have a strong brand yet a weak reputation, which is the case with many pharmaceutical companies, and which many reputation measurement surveys fail to account for when presenting their results.

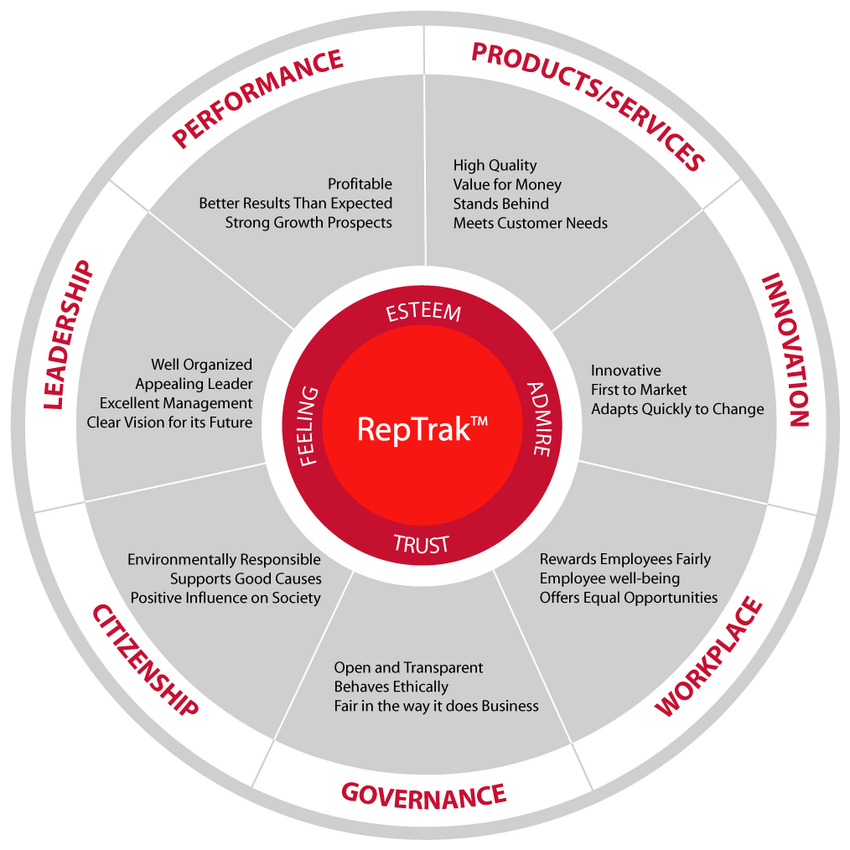

Thus one of the leading global corporate reputation measurement surveys RepTrak, carried out by the Reputation Institute, concludes in its 2017 Global Pharma RepTrak report that the reputation of the Phrama Industry is strong and improved, unlike previous years of average and even slightly declining ratings, and unlike the low general public’s perception of the industry, being blamed for: failure to assist patients in securing medications in a difficult economic environment; offering drugs with short-term health benefits; not serving the needs of marginalized patient groups; inappropriate marketing of drugs; unfair pricing policies; lack of transparency in corporate activities; etc.

Figure 2: RepTrak Framework

RepTrak™ Reputation Model (Reputation Institute, 2017) RepTrak is the standard measurement that was developed by Charles Fombrun who provided a measurement of the views of public on the reputation of world’s best-known companies. This reputation model provides companies with a standardized framework for benchmarking their corporate reputations internationally and to enable identification of factors that drive reputations. The RepTrak™ model measures on four (4) important core areas which are trust, esteem, admire, and good feeling (Figure 1) from the stakeholders perceptions towards the company (Reputation Institute, 2017). The reputation is built on seven (7) dimensions or facets namely, products/services, innovation, workplace, governance, citizenship, leadership, and performance (Reputation Institute, 2017).

Source: Reputation Institute

Far be it from me to comment on the RepTrak methodology, the research findings present a good starting point for deconstructing pharma reputation and defining its real drivers. The overall strong pharma reputation, as reported by the 2017 Pharma RepTrak, consists of average performance across two dimensions, namely Governance and Citizenship, and strong performance across the remaining 5 dimensions- Leadership, Financial Performance, Products, Innovation, and Workplace (see Figure 2 for description of the dimensions).

In the context of pharma’s reputational challenges, some of which were highlighted above, it seems that the general public’s perception depends on both the past experience people have had with a company and the extent or nature of their communication with it through the media and word of mouth. As a rule of thumb, when the public has no direct experience with a company, the impact of media coverage on public knowledge and opinion of that company increases.

When speaking about corporate reputation in the pharmaceutical industry, it is usually not the products that prompt people to say positive or negative things about a company, but rather people’s perception of the company formed by past experience or media coverage. In this regard, Governance and Citizenship, to use the RepTrak terminology, are arguably the main drivers of pharma reputation.

At this point in the discussion, it is useful to reestablish the link between brand and reputation. Governance and Citizenship are very much ‘personality-based’ constructs, which brings us back conveniently to branding. The 2017 Global Pharma RepTrak research has identified the following top 3 brand personality traits with the biggest impact on reputation:

Figure 3: Pharma Brand Personality Associations

This finding confirms that a strong brand with positive reputation must be trusted by its stakeholders, i.e. trustworthiness is the single most important driver of corporate reputation.

Pharma Communication: Going Back to Basics

If stakeholders’ perceptions of pharma companies are influenced primarily by the media due to the lack of direct experience with those companies, then pharma needs to reconsider their public relations strategies and shift their focus from the dissemination of information through press releases to entertainment education and persuasion, and finally to the achievement of mutual understanding with their publics.

To do that, you need to adapt agenda setting and framing– the two mass communication theories most relevant to pharma- to the changing media landscape.

Agenda setting is related to the idea that media don’t tell people what to think, but what to think about, whereas framing, which can be viewed as a second-order agenda-setting, deals with the idea that people use sets of expectations to make sense of their social world and media contribute to those expectations.

Unlike the 60s when these two theories were first developed, the modern media landscape is populated by bloggers, citizen journalists, Facebook and Twitter users, alternative media outlets, as well as traditional media giants. Today, as a result of advancements in technology-e.g. cheap ways of creating and distributing content-anyone can become a node in the media production process. Thus a major task for pharma communication professionals is to monitor the effect of the redistribution of power between traditional media “gatekeepers”, and social and online media sources, on pharma companies’ agenda building potential, i.e. their ability to build the agenda for the different media constituencies.

One way to achieve this is to carry out a socio-demographic analysis per country of periodically repeated population surveys on media consumption such as Univox or Mediascope so as to find which media channels the general population uses to inform itself about health, and which media outlets are considered trustworthy regarding this issue.

The cross-pollination effects of traditional and social media lead to traditional media regularly citing blogs as source material– and blogs largely relying on traditional media for information as well. For example, much of the content that gets retweeted and goes on to trend on Twitter is generated by traditional media outlets, and more recently, especially in the US, by alternative media outlets; so ironically, one of the best ways to influence the conversation on Twitter is to influence the traditional media, something that pharma companies are well poised to do in views of their traditional media orientation.

In the context of the changing media landscape where many people hear about medical discoveries for the first time through popular media, there are two major issues for pharma media relations with direct effect on stakeholder’s perception of the industry: lack of journalist expertise about healthcare and the inaccurate reporting of medical news.

The declining expertise of journalists with relevant expertise about an industry involved in the complex process of the creation, development and provision of medicine, means that media coverage of pharma industry issues is increasingly less likely to present a balanced view, particularly with regards to new drug therapies, drug pricing, marketing, and conflict of interest.

The accuracy and comprehensiveness of pharma industry coverage are important for multiple stakeholders, especially patients, healthcare providers, and payers. In this regard, however, the media often overemphasizes the benefits of new drug therapies through inadequate reporting of side effects, or conversely, overemphasizes the rare negative effects of a study’s findings. Such preliminary coverage usually sets the tone for subsequent news stories with potential to impact demand (positively or negatively) for particular treatments, which in turn can affect payers’ and providers’ decision-making.

From a PR strategy point of view, pharma relies almost exclusively on press releases for the dissemination of important corporate news and announcements. While press releases are a great way to summarize key information in a digestible fashion and frame important issues in a positive/neutral light, the use of PR distribution services and databases to disseminate them is not the best way to get your story in front of reporters because the latter just ignore them.

The benefit of targeting influential reporters with expertise in pharma with tailor-made messages will far outweigh doing a blast with a standard press release sent out to your entire journalist database. So don’t send your most influential journalists standard press releases! Why would they read them? They wouldn’t care about you more than they would care about the 100 other firms that attack them with press releases.

When it gets to measuring communications strategy effectiveness, counting press release penetration as actual media pick-up fails to account for the company’s specific communications objectives. As there are two key groups of recipients of PR messages- the media as an initial recipient, which, in turn, serves as the conduit for transmitting messages to the intended target audience, often times each of these groups is in a different stage of the firm’s communications cycle, and may have different communication needs. In such cases, it is necessary to carry out media content analysis in order to identify specific messages picked up by the media, and use them to discover gaps or misstatements in the coverage that need to be corrected.

Alternative Media Narratives: How Can Pharma Fight Conspiracy Theories?

As mentioned earlier, alternative media outlets are already occupying a significant niche in the media landscape, especially in countries such as the US. Unsurprisingly, such media outlets stay off the radars of pharma corporate communications departments. However, in the context of the declining trust towards mainstream media as reported by the 2017 Edelman Trust Barometer, one cannot deny their rising influence on public opinion, attitudes and behaviour, making the public more vulnerable to fears.

Some of these fears are related to healthcare and pose a growing challenge to pharma communications. For example, recent research by the University of Washington has found that there is convergence within the alternative media outlets around a number of “conspiracy” themes: in addition to anti-globalist and anti-media views, those outlets increasingly published content that was anti-vaccine, anti-GMO, and anti-climate science.

With regards to anti-vaccine information, studies have identified two emerging trends: a rise in conspiracy theories following the 2009 H1N1 epidemic threat which is claimed to have been “manufactured” by vaccine suppliers and allied players, and the increased use of anti-vaccine testimonials by “experts” (e.g. unidentified doctors). A similar pattern of alternative media narrative creation also covers other areas of importance to patients and pharmaceutical companies.

Understanding the dynamics of alternative media, where the same content appears on different sites in different forms, combined with what is known about how believing in one conspiracy theory makes a person more likely to believe another, led the researchers from the University of Washington to suggest that alternative media outlets may be acting as a breeding ground for the transmission of conspiratorial ideas. In this way, a “critically thinking” citizen seeking more information to confirm their views about the danger of vaccines may find themselves exposed to and eventually infected by other conspiracy theories about pharma and health issues, with one conspiracy theory acting as a gateway to others.

Multiple studies have found out that the traditional strategy of fighting anti-vaccination information with education and evidence-based communication has proven ineffective. This is generalizable to fighting all public misconceptions about treatments where there is high perceived risk on the part of patients.

Alternative strategies that have proved effective include emphasizing ‘simple bottom line meaning’ instead of facts and details, including more emotionally compelling content and absorption into a media narrative as a mechanism to influence one’s real beliefs and behaviours. This recently developed narrative persuasion theory seeks to achieve engagement with a media narrative through transportation, perceived similarity to characters in the story, and empathetic feeling toward those characters.

The persuasive power of media narratives to produce attitude change in health-related situations can be illustrated by the following example, where a group of researchers at the University of Southern California compared the effectiveness of a specifically prepared narrative video (The Tamale Lesson) and a non-fiction narrative including doctors, health experts, and data charts (It’s Time) in spreading information about cervical cancer and the need for Pap tests.

Although both were successful in raising awareness of cervical cancer and creating positive attitudes toward testing, the fictional narrative was more effective, especially as viewers’ level of transportation into the narrative increased.

A different, much more dramatically constructed and presented media narrative, a six-episode-long storyline in the network television show Desperate Housewives that focused on non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (blood cancer), was found to be effective in linking involvement with a specific character (Lynette Scavo) and the narrative itself with increased knowledge and even behavioral intention in the form of further information seeking and talking to friends and family about cancer.

Pharmaceutical companies can therefore use entertainment education to embed prosocial messages in popular media content, either with the specific intent of influencing attitudes or behavior and overcoming various forms of resistance, or simply as a dramatic device, but one that serves incidentally to promote a health-related end.

In this regard, a major advancement in communication theory is the creation of the entertainment overcoming resistance model by Emily Moyer-Gusé, whose basic premise is that “features of entertainment media that facilitate involvement with characters and/or narrative involvement should lead to story-consistent attitudes and behaviors by overcoming various forms of resistance.”

Concluding Remarks

Although it is the actions of pharma companies that have hampered their reputations, their messaging has also played a role. The problem of messaging can be viewed from two angles: message source credibility and message content.

Public relations professionals in the pharmaceutical industry have traditionally relied on the CEO as the main spokesperson when communicating important corporate news and announcements. The source credibility of CEOs, however, is plummeting, as indicated by the Edelman Trust Barometer shown below.

Figure 4: Source Credibility of Spokespeople

Source: 2017 Edelman Trust Barometer

Therefore, a change in spokespeople when and where appropriate, for example using experts or executives grounded in science, or even ordinary people (“a person like you”), can help pharma companies reduce their target audiences’ reactance and selective avoidance.

With regards to message content, the industry needs to use entertainment education and storytelling whenever possible to facilitate involvement with characters and absorption in the narrative, which could enhance persuasive effects and reduce counterarguing if the story’s persuasive content is counter-attitudinal.