The spread of vaccination-related conspiracy theories has become a key subject of study for media researchers, social psychologists and medical professionals. The phenomenon has also emerged as a pressing concern when it comes to reputation management in the pharma industry. In order to gain deeper insights into the issue, we analysed the recent conversation around vaccination on traditional and social media.

Hardly any part of the pharma market is more inextricably intertwined with conspiracy theories than the vaccines sector. The efficacy and alleged dangers of vaccination are among the most intensely debated subjects on a variety of media channels, in spite of the fact that vaccines are scientifically recognised as one of the greatest achievements of public health. Researchers examining the determinants of vaccination decision-making have called this phenomenon “vaccination hesitancy”, suggesting that it significantly contributes to decreasing vaccine coverage and an increasing risk of vaccine-preventable disease outbreaks and epidemics.

Study after study has suggested that the media (and social media in particular) is to blame for giving a platform to anti-vaccine groups who often recycle long-debunked theories about links between vaccination and autism. Most recently, a report by the Royal Society for Public Health (RSPH), sponsored by US pharmaceutical company Merck, concluded that up to half of parents are exposed to negative messages about vaccines on social media. Meanwhile, the World Health Organisation (WHO) ranked “vaccine hesitancy” as one of 2019’s top 10 global health threats, alongside climate change and HIV.

A historical perspective

Public debates around the medical and ethical issues related to vaccination have existed since the 18th century and have gained momentum with the advent of mass media in the 20th century, when health professionals started to engage in communicating the importance of immunisation.

The prevalence of media images portraying vaccines increased after the introduction of the diphtheria vaccine in the 1920s, and in the 1950s, health officials started involving key opinion leaders in their communication efforts. For example, photographs of Elvis Presley getting a polio vaccine were published in many newspapers across the US – a PR manoeuvre aimed at making the polio vaccination campaign more relevant to teenagers.

While anti-vaccination content was more or less marginalised during that time, the heyday of conspiracies came shortly after 1998, when the respected medical journal The Lancet published a study by British physician Andrew Wakefield, who said there might be a link between vaccines for measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) and autism. The paper coincided with already popular worries about an eventual correlation between the rising number of vaccinations and the growing number of autism cases.

Wakefield’s theory became widely fashionable in 2001, when former Prime Minister Tony Blair and his wife refused to say whether they had vaccinated their son, which was well-documented by the British media. A number of studies found a correlation between the media coverage and the outbreaks of rare diseases at that time due to declining rates of vaccination.

Conspiracy = coverage driver

The American media started following the conversation in 1999, when the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) reviewed the use of the preservative thimerosal in childhood vaccines and recommended removing it as a precautionary measure, although it found no evidence of harm. The debate was fueled in 2000 by Dan Burton, a former Republican Congressman from Indiana, who claimed that vaccines caused his grandson’s autism and asked the Department of Health and Human Services to examine the alleged connection between immunisation and the developmental disorder.

In this way, Wakefield’s theory began to drive more coverage, with journalists rarely emphasising that the autism hypothesis is not a legitimate scientific debate. This could be attributed to the scaling back of dedicated science journalists and the fact that the quality of mainstream science reporting has been generally low. In the US, most medical news stories have failed to adequately address issues such as quality of scientific evidence and a medicine’s benefits and harms, as a study by the University of Minnesota School of Journalism and Mass Communication found.

The conspiracy’s influence was exemplified by a large measles outbreak in Indiana in 2005, which occurred because many families declined vaccination after reading media reports of the putative association between vaccinations and autism.

That same year, the conspiracy was legitimised by high-profile outlets Rolling Stone and Salon, which published an article by Robert Kennedy Jr. alleging that the federal government covered up the danger of vaccines. In the meantime, some journalists started to specialise in “investigating” the side-effects of immunisation – for instance, Dan Olmsted, a senior editor at United Press International, launched the website Age of Autism, a “Daily Web Newspaper of the Autism Epidemic”, which has established itself as one of the most popular outlets for anti-vaccination content.

There have also been a number journalists dedicated to combatting the conspiracy – for instance, British investigative journalist Brian Deer wrote a series of articles about the inaccuracies in Wakefield’s work. As a result, the British General Medical Council discredited Wakefield, accusing him of carrying out an “elaborate fraud”.

“Balanced” coverage?

In a bid to be “balanced” and “objective”, many media outlets have framed the conversation around vaccination as a binary debate with pro- and contra-perspectives. Such journalistic practices are widespread in reports on morally-charged political and social issues – for instance, gun control or abortion. When writing on such polarised subjects, most top-tier publications usually try to provide equal exposure to arguments from both sides of the respective debate.

But while this might be a good press practice for political and social matters, it certainly doesn’t work well with reporting on hard scientific evidence. Adopting a “balanced” journalistic approach towards such inherently one-sided and uncontroversial cases creates the impression that there is a real debate among scientists while actually, the scientific community is in a consensus.

In the case of vaccines, a study by Cornell University found that between 1998 and 2006, 60% of articles in British media and 49% in American media have tried to be “balanced” by giving voice to both pro- and contra- arguments. And a subsequent study by Columbia University found that readers of “balanced” articles are far more likely to think that there’s a link between vaccines and autism than readers of one-sided articles.

Fueling hesitancy

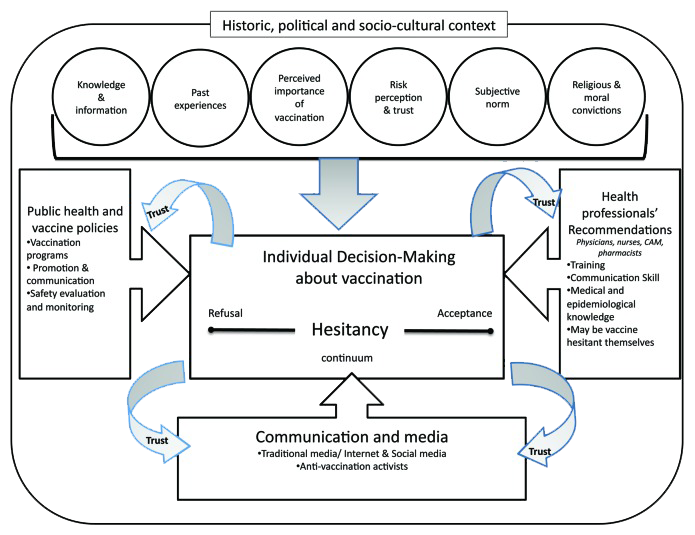

The figure below presents a conceptual model of vaccine hesitancy at the individual level and illustrates the key role of the media. There are scarcely any other examples of a public health area in which the media’s influence is viewed as a main decisive factor and is analysed on par with the influence of health professionals and health policies.

In addition to the aforementioned “balancing” problem of traditional media, conspiracy theories make their way to people’s minds via a large number of websites with exclusively anti-vaccination content. It has been estimated that the probability to encounter an anti-vaccination website is higher than the probability to encounter a pro-vaccination one.

This is especially alarming since online media has become an essential source of health information and is consulted far more frequently than healthcare professionals: in the US, 80% of Internet users have searched for a health-related topic online. It has also been estimated that accessing vaccine-critical websites for 5 to 10 minutes increases the perceptions of vaccination as risky.

Anti-vaccination websites employ similar strategies to disseminate their messages, such as citing fake experts, fabricating evidence, using logical fallacies or telling emotional stories about vaccination “victims”.

The recent conversation

It’s no surprise that conspiracy theories continue to be the most prominent topic in the vaccination media conversation. In our own analysis, in which we studied the discussion from October 2018 to April 2019 in the top-tier English-language publications, we found that conspiracies significantly overshadowed other topics:

Because our sample was limited only to top-tier publications such as the BBC, Reuters, the New York Times, CNN, Bloomberg and so on, we didn’t come across actual anti-vaccination articles, as this type of content tends to be published in lower-rank outlets. However, the impact of conspiracy sources could be deduced by the most popular stories within the ‘conspiracy theories‘ topic, as they frequently warn against the spread of misinformation. For example, numerous reports on a measles outbreak in the US emphasised the dangers of the anti-vaccination movement.

Most high-profile publications focused on WHO’s decision to rank “vaccine hesitancy” as one of 2019’s top 10 global health threats and even demonstrated commitment to combat deceiving information. In its editorial piece “How to Inoculate Against Anti-Vaxxers”, the New York Times called on the government to launch a “bold and aggressive” pro-vaccine campaign which would feature “tightening restrictions around how much leeway states can grant families that want to skip essential vaccines.”

There were also stories which fell under both ‘conspiracy theories’ and ‘research/studies’ topics – for instance, many publications reported on a new study by the University of Copenhagen which showed that the MMR vaccine isn’t associated with an increased risk of autism even among kids who are at high risk because they have a sibling with the disorder.

No way around tech

The top trending stories focused on social media’s role in dealing with conspiracy theories. For instance, Facebook plans to lower the rank of pages and groups that proliferate vaccination-related false information. In a blog post, Facebook’s vice president of global policy management Monika Bickert said that the company will begin rejecting ads that include false information about vaccinations.

The move came after the Daily Beast reported that more than 150 anti-vaccine ads had been bought on Facebook and were viewed at least 1.6 million times, and after The Guardian found that anti-vaccination information often ranked higher than accurate information.

These developments have put tech companies under the spotlight:

Google announced that it changed video recommendations on YouTube to eliminate videos with “borderline content” that “misinform users in harmful ways.” Twitter, on the other hand, has not made any specific changes and actually received some bad publicity when it was reported that its CEO Jack Dorsey appeared on a podcast with anti-vaccine fitness writer Ben Greenfield.

Amazon has started removing anti-vaccine documentaries from its video streaming service after a CNN Business report which pointed out that the company offers films such as “We Don’t Vaccinate!”, “Shoot ‘Em Up: The Truth About Vaccines” and “Vaxxed: From Cover-Up to Catastrophe.” The retail giant also removed from its online marketplace books containing pseudoscientific autism claims after a report in Wired.

The effectiveness of the CNN and the Wired reports has showcased journalists` dedication to handle vaccine misinformation proactively. Analysing the most recent conversation and comparing it with the trends in the past discussed above, we noticed a shift in the way the media presents vaccination.

Instead of framing it as a debate with pro- and contra-arguments, all top-tier outlets have made clear that vaccination is necessary and misinformation should be eradicated. Calling on policy-makers and corporations has become a common practice among journalists willing to be active in the fight against falsehoods.

Pharma`s role

Sanofi dominated the conversation with its vaccines division Sanofi Pasteur, the world’s largest vaccine manufacturer, which combines the pharma giant’s corporate brand with the product family brand Pasteur to leverage the equity of renowned French biologist Louis Pasteur.

The company featured in many stories within the ‘trials/approvals’ topic. For instance, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) accepted a Biologics License Application for Sanofi Pasteur’s dengue vaccine, the world’s first against that disease, while the European Medicines Agency said it had adopted a “positive opinion” of this new product. Meanwhile in ‘legal issues’, the Philippine Department of Justice said in March that it has found probable cause to indict officials from Sanofi and Philippine health officials over 10 deaths it said were linked to use of a dengue vaccine.

Sanofi was also the focus of ‘regulation/policy’ stories: for example, it has plans to fly flu vaccines into the UK if other transport routes are disrupted after the country leaves the EU. Hugo Fry, the managing director of its UK arm, told BBC Radio 5: “We prepare in different ways and have prepared many different routes into the UK. If we have to in the end, we will airlift it in. We are eating the cost of that but patients and citizens are our primary concern, so we’re quite happy to take that cost and make that planning.”

Both Sanofi and Merck featured in financial news for reporting higher-than-expected profits powered by sales of vaccines. Merck was also in the centre of articles on the US measles outbreak by saying it has increased the production of vaccines to meet an uptick in demand. It was also mentioned in relation to Congo’s recent Ebola outbreaks as it’s the leading Ebola vaccine manufacturer. Merck’s head of vaccines clinical research, Beth-Ann Coller, told Reuters that the company is engaged with the World Health Organization and with groups like vaccines alliance GAVI to understand what will be an appropriately sized stockpile of Ebola vaccine doses in the future.

However, pharma companies have not played a particularly active role in the battle against vaccine misinformation. They were mentioned within the ‘conspiracy theories’ topic as examples of vaccines manufacturers but they didn’t have a share of voice in that part of the vaccination discussion.

Spokespeople

The most prominent spokespeople in the conversation also didn’t include pharma representatives:

The most frequently quoted spokesperson, teenager Ethan Lindenberger from Ohio, made headlines for getting vaccinated despite his family’s wishes. He testified before Congress, explaining his decision to vaccinate himself against his mother’s wishes. Lindenberger said his mother often cited unreliable sources primarily through Facebook: “For certain individuals and organizations that spread this misinformation, they instil fear into the public for their own gain selfishly, and do so knowing that their information is incorrect.”

Dr Sanjay Gupta, CNN’s chief medical correspondent, owes his prominence in the discussion to the fact that CNN has been particularly active in covering the battle against conspiracies and quotes Gupta’s opinion in its reports. For instance, he has highlighted that the side effects to vaccines are extremely rare: “You are 100 times more likely to be struck by lightning than to have a serious allergic reaction to the vaccine that protects you against measles.”

Washington Governor Jay Inslee declared a state of emergency after 35 cases of measles cropped up in a single county, where nearly a quarter of kids at school are without measles, mumps and rubella immunisation. When discussing the measles emergency, New York Mayor Bill De Blasio warned that residents have 48 hours to get the vaccine or face a $1,000 fine, and defended the decision against potential legal challenges: “We are absolutely certain we have the power to do this. This is a public health emergency.”

US Representative Adam Schiff contributed to the pressure on Facebook and Google by sending them a letter saying that as Americans rely on their services as a primary source of information, it is vital that they “take responsibility with the seriousness it requires, and nowhere more so than in matters of public health and children’s health”. He also wrote an open letter to Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos, sharing his concern “that Amazon is surfacing and recommending” anti-vaccination books and movies.

The fact that all of the most prominent spokespeople in our sample emphasise the importance of vaccination confirms that there has been a shift in the way the media frames the vaccines conversation. The articles focused on the vital importance of immunisation and readers were rarely exposed to opinions expressed by anti-vaccination activists.

On social media

The Observatory on Social Media, a joint project of the Indiana University Network Science Institute (IUNI) and the Center for Complex Networks and Systems Research (CnetS), has spent years tracking the diffusion of misinformation on social media, including vaccination-related conspiracies.

Their most recent finding is that pro-vax information and activity is beginning to push back against, and even overtake, anti-vax disinformation. Until around 2017, the Twitter discussion was dominated by people who opposed vaccinations, but this appears to have reversed – vaccine hesitation content is now shared only by a minority of users.

Our own social media research has reached a similar conclusion. Identifying the most influential individuals and organisations in the Twitter conversation, we found that the pro-vaccination content significantly outperforms conspiracy theories. The majority of the most influential accounts belong to pro-vaccine organisations, media outlets and vaccine advocates.

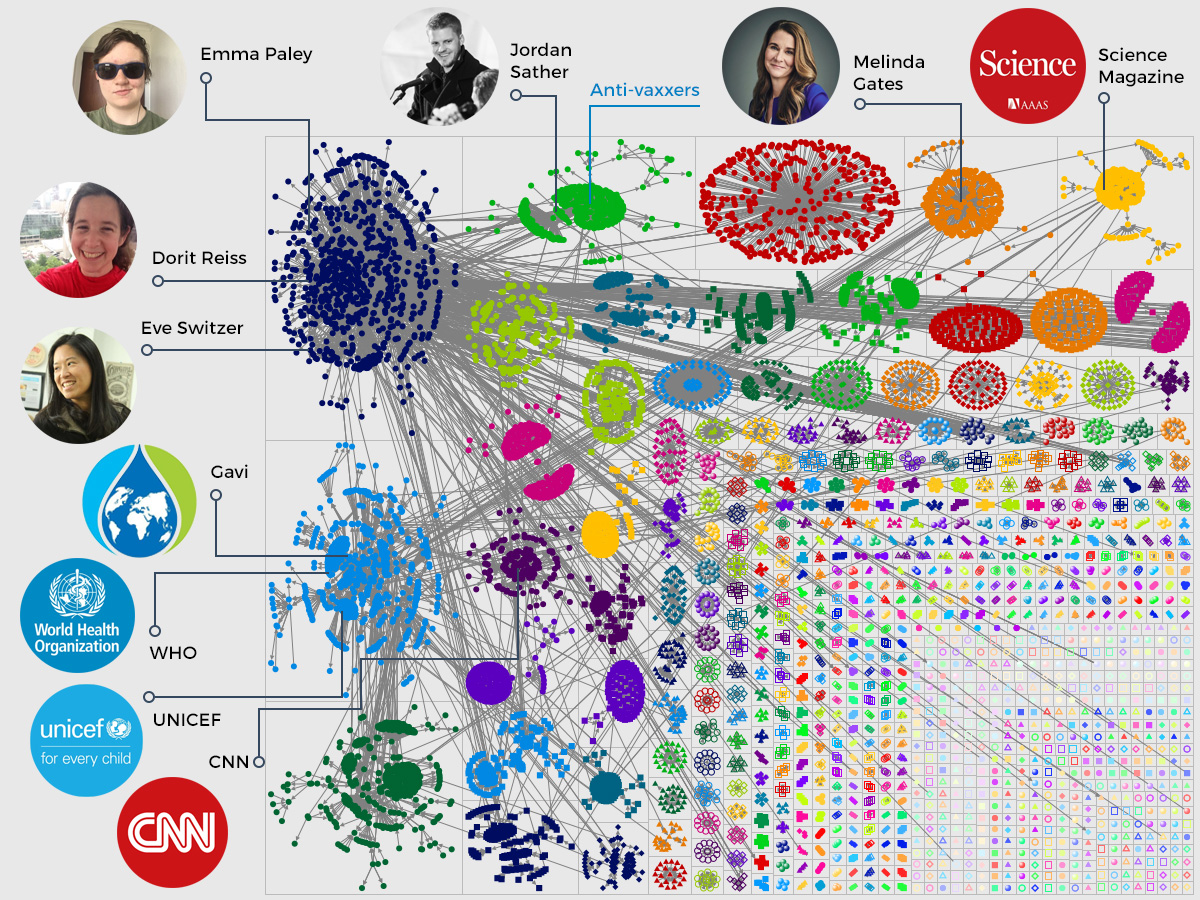

We studied a sample of 28,360 tweets from 22 to 23 April 2019 using social network analysis, an analytical method which examines the structures and patterns of the relationships between participants in a social network by looking at the ‘nodes’ (or ‘vertices’), representing the Twitter users participating in the dicussion, and the ‘ties’ (or ‘edges’) between them, representing actions such as retweets, mentions, or replies.

To analyse the structure of the Twitter discussion around vaccines, we have visualised the interactions between the participants in the discussion, i.e. the network of Twitter users, in the form of a cluster map (see below). One of the aims of social network analysis is to identify the influencers in a particular network, with “influence” broadly defined as “the potential of an action of a user to initiate a further action by another user” (Leavitt, Burchard, Fisher, & Gilbert 2009).

In this regard, we focused on the vertices (users) with the highest in-degree centrality score. In-degree centrality determines the number of incoming ties, i.e. the number of mentions and replies to a particular Twitter account in the network. The higher the in-degree centrality score, the more influential a particular node is.

Looking at the cluster map above, we might say that the structure of the conversation around vaccines resembles a broadcast network (as per Pew Research Center’s terminology). Broadcast networks consist of one or two dominating clusters (hubs) and a number of smaller clusters of users discussing different aspects of the subject. The dominating clusters comprise media outlets or influencers, surrounded by spokes of people who engage with their messages.

The hub dominating the discussion was the dark blue cluster in the top left corner. Its influencers discussed the need for immunisation and confronted conspiracy content shared by anti-vaxxers. The top mentioned users in this cluster were history student Emma Paley (@EmmaGPaley), who is also an autism patient; law professor Dorit Reiss (@doritmi), who specialises in issues related to vaccines and law; and Eve Switzer MD, (@kidoctr), Fellow of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

The active debate in that cluster was due to the many pro-vaccination replies to anti-vaxxers. The top replied-to users included anti-vaxxers @Lovelyy_Jules, who described herself as an ex-vaxxer; Forrest Maready (@forrestmaready), author of the conspiracy book “The Autism Vaccine”; and Neville Raymond (@epochchanger) another conspiracy author, whose latest book was “The Reparenting Revolution”.

A hallmark of Broadcast Network maps is that Twitter users in different groups use similar hashtags and words. We can detect the overarching pro-vaccination sentiment of the whole conversation by the fact that most often used hashtag across the clusters was #VaccinesWork.

There was only one cluster of anti-vaccination activists (the small green one next to the dominating dark blue cluster) which was quite densely structured and segregated from the other clusters, indicating that the messages within that group are not generally retweeted by users from the other groups. In Broadcast Network maps, more densely interconnected clusters are composed of small communities of interconnected users discussing the hub of the Broadcast Network with one another.

The most influential individual in this cluster was anti-vaccination campaigner Jordan Sather, who has branded himself as a “renowned educator, filmmaker, YouTube influencer, speaker, and inspiration to thousands of people wanting to become stronger, more conscious versions of themselves” and has amassed “hundreds of thousands of subscribers and millions of content views” through his online media brand Destroying the Illusion.

He regularly tweets that vaccines cause autism, often without even trying to justify his claims in some way. Most recently, he shared an article on the €2,500 fines anti-vaxx parents in Germany face and commented that “some bad actors are struggling for cash, so they’re letting mandatory vax legislation and these stories roll through for some Pharma checks,” specifically mentioning Merck, which has its roots in Germany.

However, Sather is closely followed by Melinda Gates, who regularly tweets about the need for vaccination. Most recently, she said that all three of her children are fully vaccinated and that when fewer people decide to get vaccines, we all become more vulnerable to disease. She also shared an article on the contributions of women in immunisation throughout history, which was published on VaccinesWork.org. This website is a community blogging platform powered by Gavi and its content was among the most commonly shared in the discussion.

The most influential organisations were @WHO, @UNICEF and @gavi, all of which play an important role in all stages of the vaccine value chain. Their messages often feature statistics which highlight either the past successes of immunisation programmes or emphasise the need to step up vaccination efforts and to battle misinformation. There were no prominent pharma companies in the conversation.

The top trending article in the discussion was CNN’s “MMR vaccine does not cause autism, another study confirms”, which has 21.2K Twitter shares by now, followed by Science Magazine’s “Here’s the visual proof of why vaccines do more good than harm”. Science Magazine and CNN, which follow closely the developments in the immunisation world and have devoted themselves to combatting misinformation, were also the most influential media outlets in the discussion.

Communication objectives

The pharmaceutical industry’s damaged reputation has facilitated the spread of conspiracy theories: a popular belief among anti-vaxxers is that Big Pharma conspires to hide the evidence for the relationship between vaccination and autism.

This was recently exemplified at a rally in Washington state to defeat legislation aimed at eliminating personal vaccine exemptions, at which many protestors held signs saying “Separate pharma and state”. Meanwhile, Bernadette Pajer, head of the anti-vaccination group Informed Choice Washington, recently said: “I know vaccines are designed to protect children from infection, but they are pharmaceutical products made by the same companies that make opioids.”

As vaccine advocates point out, most people don’t realize that vaccines are the least profitable division of the companies that make them and in fact, many drug manufacturers walked away from producing vaccines years ago due to low profits. In comparison to other product divisions, vaccine product lines are modest even for the largest vaccine makers.

But even though vaccines don’t constitute a major part of their business, pharma should approach the matter from a reputation management standpoint and engage more actively in communicating the need for vaccination. Companies can capitalise on the shift on both traditional and social media and on the experience other stakeholders have had in conveying pro-immunisation messages.

For instance, it has been established that the traditional strategy of fighting anti-vaccination information with education and evidence-based communication has been ineffective (Parikh 2008; Reyna 2012; MacDonald et al. 2012; Caplan 2011) as it doesn’t induce a change in behaviour among the sceptics. Although providing evidence-based information is necessary, behavioural change is a complex process which entails more than having adequate knowledge about an issue, as communication research has demonstrated.

Alternative strategies include highlighting “simple bottom-line meaning” instead of facts and details (Reyna 2012), underlining the moral obligation to act as a member of a community (Caplan 2011), producing more emotionally compelling content (Bean 2011), which could feature stories about vaccine-preventable diseases (Parikh 2008), and enhancing the knowledge of the vaccine safety system (MacDonald et al. 2012),

Perhaps the most relevant strategy would be to increase the engagement of health professionals and other vaccination advocates across media channels (Nicholson and Leask 2012). As Edelman’s Trust Barometer recommends, every healthcare company must “activate the chorus” to tell its story because the voices of authority within the industry have regained credibility.

The percentage of consumers who trust spokespeople has risen: the most credible voices of authority are technical experts (trusted by 63% of consumers) and academic experts (trusted by 61%). But spokespeople should not assume that the messages they convey to the informed public will trickle down to the mass population – instead, they should target a wide array of stakeholders.

For more on this topic, read about the role of influencer mapping in reputation management.