“We are determined to generate long-term, sustainable returns for shareholders and restore the reputation of Deutsche Bank,” said Christian Sewing, Deutsche Bank’s CEO, in a statement announcing a radical transformation of Germany’s biggest lender. The proclamation made global headlines across a wide spectrum of media outlets, prompting a flood of analyses into the bank’s strategy and the state of the financial services industry as a whole.

The corporate metamorphosis will include cutting 18,000 jobs – one-fifth of Deutsche’s global staff – the bulk of which from the global equity and investment banking divisions. The move is part of a narrative shift away from competing with Wall Street giants and back to the lender’s corporate and trade-finance roots.

The CEO’s emphasis on restoring the reputation comes after the bank’s name suffered some severe hits over the past few years, including money laundering allegations, failed merger talks, failed US bank stress tests, downgrades to its investment-grade ratings, police raids and lawsuits by Donald Trump. These mishaps led to many media outlets asserting that Germany’s biggest lender has a global reputation for scandal.

The maelstrom of negative news has caused critical damage to Deutsche’s share price, with the bank losing $14.8 billion in market value between 2009 and 2018. Furthermore, 25% of investors refused to endorse the CEO’s performance over the past year and 29% voted against the chair.

Bad headlines have also hurt the bank’s global brand – according to Brand Finance, it lost 30% of its brand value and dropped from 47th to 70th in the 2019 ranking of the most valuable banking brands.

In stressing that the restructuring effort is aimed at fixing Deutsche’s reputation, Sewing’s remarks aligned with what a large part of the commentariat has been reiterating – that you can’t restore a bank’s profits when its reputation is shot to pieces.

Scandals in the media spotlight

The money-laundering allegations have been dominating the recent media conversation around Deutsche Bank, as our analysis of the top-tier English-language publications shows:

The allegations have been discussed as one of the main reasons for the bank’s fall from grace. The media conversation has been intensifying since 2017 when UK and US regulators fined Deutsche more than $630m after accusing it of failing to prevent $10bn of Russian money laundering via “mirror trades”. The company was allegedly involved in a major money-laundering operation, called the Global Laundromat.

In November last year, German police raided the bank’s headquarters in Frankfurt as part of investigations sparked by the 2016 “Panama Papers” affair. The kind of investigative journalism that led to the Panama Papers has continued to spell troubles for Deutsche – for instance, the FBI recently started investigating whether the bank complied with anti-money-laundering laws after a report in the New York Times.

The transactions were notable because they involved companies managed by Donald Trump, for whose real estate business Deutsche Bank has long been a principal lender. This relationship with the President has also been under scrutiny: the House Intelligence and Financial Services Committees subpoenaed Deutsche in April for records on Trump’s finances.

The money-laundering scandals were mentioned in the majority of analyses into the bank’s restructuring plans. When deliberating over the lender’s new strategy, most reports discussed the allegations as an essential part of the bank’s troubled history, and the ‘Money-laundering‘ topic overlapped with the ‘Restructuring/Job cuts‘ topic in many media outlets.

As nuggets of the transformation plan emerged on the media, Deutsche’s stock had been climbing, with investors generally favouring Sewing’s initiative, which was called “very deep,” “radical” but also “challenging”. But although the honesty of the plan was praised by many, there were some who doubted whether the bank’s efforts would be enough to change its narrative.

The optimism soon faded and shares started falling as details of the strategy gradually made investors and analysts more sceptical that the bank can hit its new revenue targets in the midst a costly metamorphosis, while some journalists wrote that the restructuring plan failed to impress and that the company will eventually break itself up.

The need for restructuring was perceived as a result of a combination of several factors, including inadequate management, failure to address conduct issues and troubles with the authorities. Some publications shared the view that Deutsche’s drastic retrenchment is “the latest chapter” in “a dramatic fall from grace” that has been ongoing since the 2008 financial crisis. Others went further and suggested that it’s “the culmination” of years or decades of descent into unprofitability and scandal.

A number of outlets expressed a more positive sentiment, saying that the restructuring will actually be a long road back to the bank’s old normal because it will return to its 150-year-old corporate and trade-finance roots and give up trying to become a European rival in investment banking. An even more positive media feedback remarked that the bank’s strategy is on track at last.

Industry trends

For some publications, Deutsche’s overhaul reflected the transformations taking place in the financial industry as a whole, and in investment banking in particular. The focus was on the fintech revolution, which has seen market disruptors from the technology sector competing with well-established financial players in areas ranging from payments to asset management.

While a wave of digitalisation has swept over all industries, from retail and media to construction and transport, the tendency is increasingly conspicuous in the financial services sector. “Becoming a digital business” is a top priority for financial services CIOs, as a recent Gartner research concluded. Their digital enthusiasm is far greater than the average across other industries and beats other objectives such as profit growth and consumer satisfaction.

Big players have usually relied on their established brands, but their legacy back-office structures and high regulatory standards have left them scrambling to keep up with the emerging fintech trends. Feeling the urgent need for innovation, many are looking for new ways to keep pace with the myriad of tech-based challengers.

Of course, the financial world has been subject to digitalisation since the advent of computers, but the reason for the current rush has been the market disruption caused by the booming fintech scene. This made ‘digital transformation‘ a major topic in the media discussion around banking.

In a nutshell, digital transformation is all about embracing new technology and putting this in the heart of all business practices. Doing so is estimated to bring $18 trillion in additional income worldwide, but it’s not just a matter of growth, but a question of surviving – a recent study conducted by software company SAP found that for 84% of businesses worldwide, digital transformation is crucially important to their survival in the next five years.

The growing popularity of fintech solutions has also been facilitated by the post-2008 distrust in major banking institutions. Deutsche Bank was among those who were hit the hardest by the impact of the Great Recession, alongside Merrill Lynch, JP Morgan, Citigroup, RBS, Wells Fargo, Goldman Sachs, Credit Suisse and Morgan Stanley.

But while banks such as Goldman Sachs and Wells Fargo have been recovering quite well, having made more in cumulative profits in the past 10 years than in the previous decade, Deutsche has lagged behind. In 2017, it signed a $7.2 billion settlement with the US Department of Justice for selling investors bad mortgage-backed securities between 2005 and 2007.

Some journalists noted that the scene at Deutsche Bank buildings amid the job cuts looked eerily familiar to 2008 when axed workers were leaving their offices carrying boxes with their belongings.

The years following the 2008 crisis have reinforced the public’s hostility towards Wall Street: for many consumers, the word “banker” became a synonym of a fraud. Research by management consulting company Gallup concluded that confidence in banks had dropped from 53% in 2004 to 21% in 2012, while 64% of the respondents in a Harris survey said that bankers didn’t deserve their huge paychecks.

The crisis posed unprecedented challenges to communication professionals – in the past 10 years, the lion’s share of their work has been revolving around the reconstruction of the shattered image of financial institutions. In a bid to restore trust and confidence, the world of finance is in an ongoing process of redefining itself.

Keeping up with the Joneses

German Commerzbank, which has also been dealing with financial troubles, was the most often mentioned company in our research sample:

The Commerzbank’s dominance was due to the abundance of reports on its abandoned merger talks with Deutsche, which was deemed by both banks as too risky. In a statement, Deutsche said the deal would have created additional risks and costs, which would outweigh the potential benefits.

The merger was perceived by many publications as a way of reviving both banks, while critics remarked that merging two troubled banks would have resulted in one big troubled bank. The failed tie-up generated significant reputational damage, with analysts seeing it as another unsuccessful attempt to restore Deutsche.

Goldman Sachs and JPMorgan were mentioned as the Wall Street investment banks with which Deutsche tried to compete with little success. The restructuring was perceived as a sign that the European bank is coming to terms with its failure to keep pace with these Wall Street giants, who also offered some thought leadership on the matter.

For instance, Goldman Sachs noted that the restructuring would be very deep by any measure: “Media reporting ahead of Sunday’s board meeting was intense, yet the announcements still surprised in terms of their scope and scale”. JP Morgan said that the planned transformation is “bold and for the first time not half-baked but a real strategic shift”.

Of the companies appearing in the media discussion, Denmark’s Danske Bank was mentioned with a particularly negative sentiment for being investigated by the US Federal Reserve’s for its role in a money-laundering scheme involving Deutsche.

Reputation analytics: a new way to measure corporate reputation through the media

Approaches to measuring corporate reputation have traditionally been fraught with conceptual difficulties of what exactly constitutes ‘corporate reputation’, and many models suffer from one-dimensional focus.

More robust models, such as the Harris Poll Reputation Quotient (RQ) and the Reputation Institute’s RepTrak, offer multi-dimensionality and attempt to analyse the link between reputation and financial performance, which is hard to prove. It seems that there is no direct correlation between stock market performance and corporate reputation at least in the short term.

These models rely mainly on survey methods to collect data about the various dimensions of corporate reputation, which makes their administration and application difficult for the purposes of ongoing reputation analysis and management. A key input into most reputation measurement models is media coverage, looking at how and what the media is covering about the company, which leads us to speak about ‘media reputation’.

The media can have a disproportionate impact on a company’s reputation due to the fact that in many industries it is the primary shaper of public knowledge and opinions about companies, especially in cases when the public does not have any direct experience with those companies or the issues surrounding them.

In this regard, we align with Deephouse (2000) proposition that a company’s media reputation can be viewed as a strategic resource, part of the intangible assets of the company, so it should be managed accordingly. Reputation analytics is thus analysing the drivers of corporate reputation as presented in the media.

A major problem with measuring reputation through the media is the reliance on manual processing of media data to identify reputation drivers and their underlying sentiment, which in spite of achieving precision and recall close to 100%, is restricted to smaller samples sizes, usually less than 1,000 articles. Recent developments in text analytics technologies, particularly natural language processing (NLP) and deep learning, have enabled the design of media reputation measurement models that produce results similar to survey-based methods.

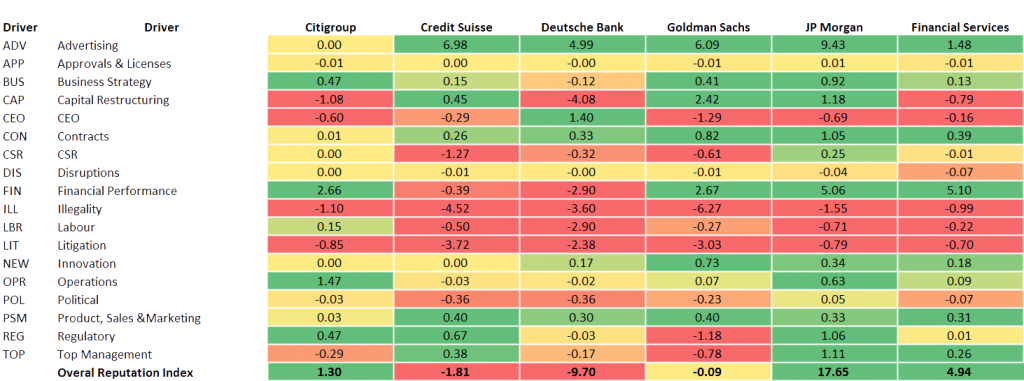

We use one such model- our proprietary reputation analytics framework ComVix– to analyse and measure Deutsche Bank’s reputation, and compare it with that of four other big banks – Citi, Credit Suisse, Goldman Sachs and JPMorgan.

While other media analytics platforms categorise entities or topics, ComVix is capable of disambiguating sentence structure to classify the business events that drive corporate reputation. Using a hybrid between rule-based NLP and machine-learning, we have developed the most granular taxonomy of business events driving corporate reputation to date, achieving precision and recall of above 90%.

A key component of our model is uncovering the sentiment at scale, i.e. uncovering the sentiment associated with each individual construct (e.g. company) within each article. Uncovering sentiment at scale and hence interpreting the drivers of reputation requires allocating sentiment with individual constructs, which most media analytics platforms doing automated sentiment analysis fail to do.

Our reputation analytics platform ComVix is able to automatically track almost 500 news-reported business events driving corporate reputation, categorized into 18 overall reputation drivers as presented below:

Finally, we base our quantitative measure of corporate reputation on Net Promoter Score (NPS), calculated as the difference between positive mentions and negative mentions per driver, to arrive at ComVix Reputation Index (CRI).

Just like NPS, CRI ranges between -100 and 100, with positive results generally deemed good, and CRI of +50 deemed excellent. The heat map below presents the CRI for Citi, Credit Suisse, Deutsche, Goldman Sachs and JPMorgan, as well as for the entire Financial Services Sector, encompassing 665 large-cap companies listed on NASDAQ. The analysis is based on 2.7 million articles for the period 1st January 2018-30th June 2019.

Unsurprisingly, Deutsche`s reputation index is pretty negativе, with an overall CRI standing at -9.70.

The strongest driver behind this score was Capital Restructuring (CAP), which stood at -4.08. The negative sentiment was a result of the many articles doubting the bank’s transformation plans, being sceptical that it can hit its new revenue targets and expressing the opinion that the restructuring plan failed to impress.

A modest degree of balance was added by the positive score of the CEO, which stood at 1.40. This was due to the common belief that while it’s too early to tell what’s going to happen, Christian Sewing should be applauded for the decisive plan.

The strength of the Capital Restructuring (CAP) driver is even more notable when taking into consideration that its score is higher than the most sensitive reputation driver for the financial services sector as a whole: Illegality (ILL).

In Deutsche’s case, this driver stood at -3.60 as a result of the numerous analyses into the money-laundering allegations, the main topic in the media discussion.

Capital Restructuring (CAP) was also closely related to Labour (LBR), which stood at -2.90 and referred to the 18 000 employees who would lose their jobs in the transformation process. Not surprisingly, Financial Performance (FIN) also contributed significantly to the negative overall CRI score, as did Litigation (LIT), which was mainly about the lawsuits filed by regulators and by Donald Trump.

The strongest reputation driver with a positive sentiment was Advertising (ADV), which mainly involved the bank’s brand and marketing campaign #PositiveImpact featuring client partnership stories and Laura Dekker, the youngest person to sail solo around the world. The campaign won Gold in the ‘Best Integrated Campaign’ category at the 2019 German Brand Awards, with the jury recognising it for its excellence in brand strategy and creation.

On the other end of the spectrum, JPMorgan was the bank with the highest CRI score (17.65). It’s strongest reputation driver with positive sentiment was also Advertising (ADV), which included brand positioning efforts such as the annual JPMorgan Healthcare Conference, which is widely perceived as the most important event in the healthcare sector.

The conference is seen as shaping the agenda for both the industry and individual companies and is often dubbed “speed dating for investors” and “the Olympics of healthcare”. This January’s gathering brought together more than 450 public and private companies, from start-ups to giants with more than $300 billion in market cap, spanning the whole global healthcare sector, including pharma, insurance and biotech.

Advertising (ADV) was the driver with the most powerful positive sentiment for Goldman Sachs and Credit Suisse as well. Goldman Sachs, for instance, was discussed in the context of its advertising campaign Marcus by Goldman Sachs which takes a more consumer-facing approach to marketing and encourages consumers from various financial backgrounds to save and invest. The bank also made headlines for its 10,000 Women campaign, which aims to support female entrepreneurs in emerging markets.

On the other hand, Illegality (ILL), the most sensitive reputation driver for the whole financial services industry, generated the highest negative sentiment for both Goldman Sachs and Credit Suisse. For example, Credit Suisse was most recently embroiled in a scandal when three of its former bankers were arrested on charges of a fraud involving $2 billion in loans to state-owned companies in Mozambique.

In a need for reputation investments

Deutsche Bank’s reputational calamities take place amid a growing distrust in the financial services sector as a whole and particularly in Europe, where the industry has struggled to grow because of its less active approach to the financial crisis.

Finance brands continue to experience reputational setbacks, taking the last place globally for overall reputation, alongside telecoms, in Brand Finance‘s rankings: brand values have fallen and customer satisfaction is at an all-time low, with three of Germany’s leading financial institutions being among the fastest declining brands by strength – Nord (-23%), Bayerische Landesbank (-19%) and Deutsche (-13%).

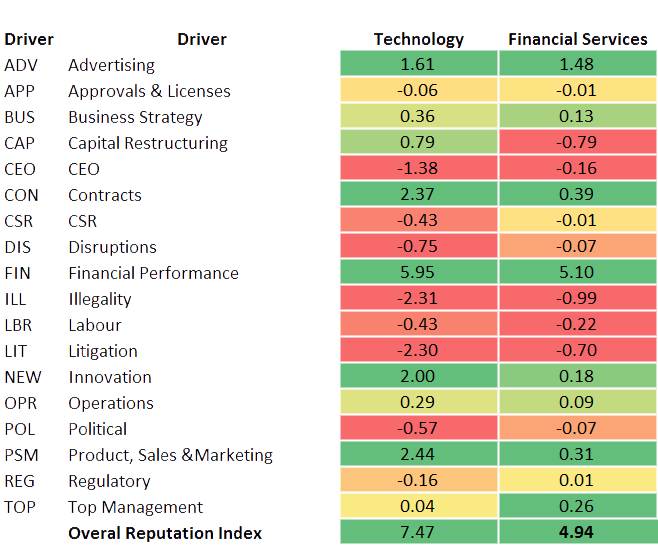

The financial services sector remains the least trusted one, as per Edelman’s 2019 Trust Barometer, which found the technology industry to be most trusted.

This difference in reputation is also highlighted by the CRI scores for finance and tech:

Tech brands have remained resilient despite recent data privacy scandals. Facebook’s troubles, in particular, were what really made data privacy a central concern for consumers – it became clear that improper handling of sensitive information can lead not only to financial abuse but can also influence global politics and people’s health and well-being.

The risk associated with the way data is used versus the way it’s safeguarded is becoming a priority for an ever-larger group of stakeholders, not just regulators and policy makers. This made Illegality (ILL) and Litigation (LIT) the most sensitive reputation drivers for the tech industry.

But in spite of this, higher scores for reputation drivers such as Innovation (NEW) and Products, Sales & Marketing (PSM) placed tech way above banking. This goes to show that the financial services sector is getting even more vulnerable to disruption from stronger tech brands.

Read our analysis “From Media Data to Reputation Analytics: A Case Study of Facebook”.