The pandemic has provided a fertile ground for the QAnon conspiracy theory – which is claiming that a cabal of Satan-worshiping paedophiles is running a global child sex-trafficking ring and plotting against Donald Trump – to move from the political fringe into the global mainstream.

Protesters at anti-lockdown and anti-mask rallies around the world are asserting that the pandemic is orchestrated by a satanist group of Democratic politicians and Hollywood moguls who actually control the world behind the scenes.

The conspiracy has found its way to the political elites: Media Matters, a media watchdog that has been tracking QAnon’s movement for the past few years, estimates that 26 congressional candidates on the ballots, mostly Republicans, have either endorsed or showed support for QAnon.

And according to a series of Pew studies, the percentage of Americans who say they have heard “a lot” or “a little” about QAnon roughly doubled from 23% in March to 47% in September, while another survey found that one-quarter of social media users who have heard of QAnon say they believe the group’s conspiracy theories are at least somewhat accurate.

Of course, social media is where it all takes place: a recent Guardian report found that about 170 QAnon Facebook groups had some 4.5 million aggregate followers. It got to the point that the FBI has labeled QAnon a domestic terrorist threat.

As a consequence, Twitter announced it would begin cracking down on QAnon content, and Facebook announced it would remove all pages, groups, and Instagram accounts that promoted QAnon. After significant pressure, YouTube announced a crackdown on QAnon although it stopped short of an explicit ban.

However, examining the discussion on Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest and Reddit during the last 12 months, we found that youtube.com was the domain with the highest number of engagements across social media channels, meaning most users consumed QAnon content via YouTube videos rather than via media outlets – especially on Facebook, which seems to have a hard time taking down misinformation.

We found that QAnon increasingly overlaps with pseudoscientific claims that coronavirus does not exist, and QAnon influencers and pandemic conspiracists have started pushing one big conspiracy narrative.

Most QAnon supporters have been sharing Plandemic, a conspiracy theory video starring discredited former medical researcher and prominent anti-vaccine activist Judy Mikovits, who suggests that, among other things, vaccines are “a money-making enterprise that causes medical harm”, the virus was manufactured and that “if you’ve ever had a flu vaccine, you were injected with coronaviruses”.

The virality of these videos continues to persist despite efforts from YouTube to demonetise content that are pushing the anti-vaccine agenda. Channels belonging to legitimate organisations, such as Vaccine Makers Project, which is committed to public education about vaccine science, and Gavi, the global health partnership increasing access to immunisation in poor countries, lag behind.

18% of pro-Trump tweets promoted QAnon

To examine how the QAnon conspiracy affected the conversation around the US election, we analysed 45,633 tweets by Trump supporters posted between 1 Jul- 18 Oct.

We found that 8,375 of these tweets referenced QAnon in some way – in other words, 18% of the pro-Trump tweets we analysed pushed the conspiracy.

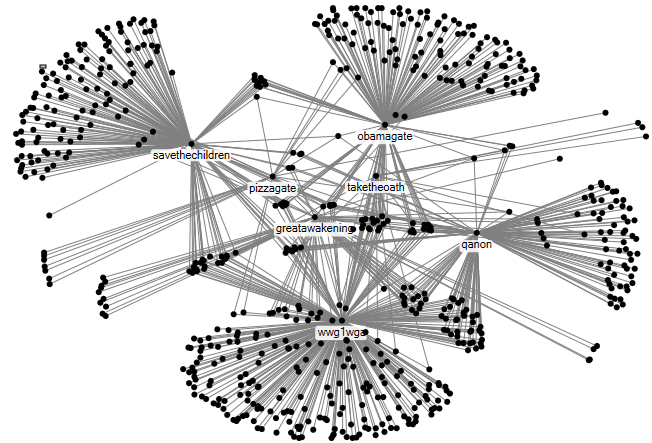

We also found that QAnon supporters often used the hashtag #WWG1WGA, signifying the motto “Where We Go One, We Go All”, which became the most influential hashtag in the conversation:

The hashtag #SaveTheChildren was also commonly used as QAnon followers believe that children are being abducted in large numbers to supply the child trafficking ring.

Our analysis also shows that the long-standing #Obamagate conspiracy theory, which was pushed by Trump’s accusations of Obama’s criminality, have also started to merge with QAnon. The theory started in May when Trump retweeted the word “OBAMAGATE!”, with the hashtag accrueing over two million tweets the next day and another four million by the end of the week.

However, the theory doesn’t provide clear allegations but rather accuses the Obama administration of a vague cover-up, relating to the investigation into collusion with Russia.

A similarly vague theory in the QAnon conversation is #Pizzagate, whose promoters claim that several high-ranking Democratic Party officials and US restaurants collude in an alleged human trafficking and child sex ring.

These hashtags have formed Community Clusters (as per Pew Research Center’s terminology) of Trump supporters.

Twitter discussion around QAnon: Most influential hashtags

Community Clusters like this one consist of multiple smaller groups, which often form around a few hubs each with its own audience, influencers, and sources of information. These Community Clusters conversations look like bazaars with multiple centres of activity.

The hashtag #GreatAwakening is an example of QAnon’s vocabulary which echoes Christian tropes, evoking the historical religious Great Awakenings of the early 18th century to the late 20th century.

According to many QAnon videos, the battle between Trump and “the cabal” is of “biblical proportions”, while the forthcoming reckoning will be a “reverse rapture”.

The religious nature of the discussion could also be illustrated by some of the most commonly used words in QAnon tweets – “Bible”, “apologetic”, “Jesus”, “Christian” and so on:

The numerous references to Israel were made by QAnon accounts which praised Trump’s peace plan to resolve the Israeli–Palestinian conflict and boosted his image as a messiah.

QAnon supporters used the #AllLivesMatter hashtag, sharing passionate disapproval of the Black Lives Matter movement and the protests following George Floyd’s killing, calling them violent riots organised by anarchists and vandals.

Many felt that the police is under attack and portrayed Trump as someone who can guarantee law and order. As such, the election was often framed as a choice between violent riots and “church, work, and school”.

Our analysis shows that QAnon represents a new kind of conspiratorial thinking. While proponents of other conspiracy theories like vaccine hesitancy or climate change denial strive to collect pseudoscientific evidence for their claims, QAnon followers don’t bother to back up what they say. In a way, the very vagueness of their accusations makes them more passionate about framing themselves as searchers for the truth.