Pharma PR and comms need new strategies to reduce the stigma around lung cancer, which gets in the way of screening rates and drug development.

Lung cancer has a branding problem

More people die from lung cancer than any other cancer, and it kills more women than breast, ovarian and cervical cancer combined. Yet lung cancer gets a fraction of the funding received for other cancers.

And the main reason for this, according to multiple studies, is stigma.

That’s because lung cancer has, as we say in PR and comms, a branding problem. And it’s one of the most pressing comms challenges for major lung cancer players like Roche, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck and Pfizer.

Over the past several decades, anti-tobacco campaigns have been successful in educating people about the link between smoking and lung cancer. There’s no doubt that many lives have been saved by these efforts.

But there’s also been an unintended consequence: lung cancer is now only seen as a “smoker’s disease” or “a dirty disease” in the public’s mind, resulting in patients feeling blamed for their condition, whether or not they have a history of smoking. That’s why compared with other common cancer screenings, lung cancer screening rates fall terribly behind.

Indeed, our analysis of circa 10,000 Reddit posts in discussions around lung cancer found that lung cancer’s most prominent brand attribute – the quality that most people associate with the brand – was “smoking-induced”:

Many users implied that lung cancer is a matter of personal responsibility, which led to patients in the discussions worrying about being blamed for their symptoms and delaying seeking diagnosis or care.

And this corresponds to how the media frames the debate, focusing on smoking and personal responsibility as the main cause of lung cancer:

How pharma can turn the tide

There have been many initiatives trying to tackle the lung cancer stigma – consider Genentech‘s recent campaign or the National Lung Cancer Roundtable‘s efforts.

The issue with these campaigns is that they focus mainly on raising awareness of stigma and the need to reduce it. Their message usually is: “You’re looking at this the wrong way, here’s the right way”.

We think there’s a better way such campaigns can be crafted – informed by advanced media analytics, melding AI with expert human analysis. Here’s where pharma can start:

1. Frame screening as a proactive measure, not a penalty

Because lung cancer is so much linked to smoking, stigma plays a significant role in preventing many people eligible for screening from pursuing it. Many people eligible for lung cancer screening fear being blamed for their previous or current tobacco use.

But framing screening as a proactive measure to help those at risk and as a collaboration with those who need help quitting smoking can empower people to actively engage in screening rather than dreading or avoiding it.

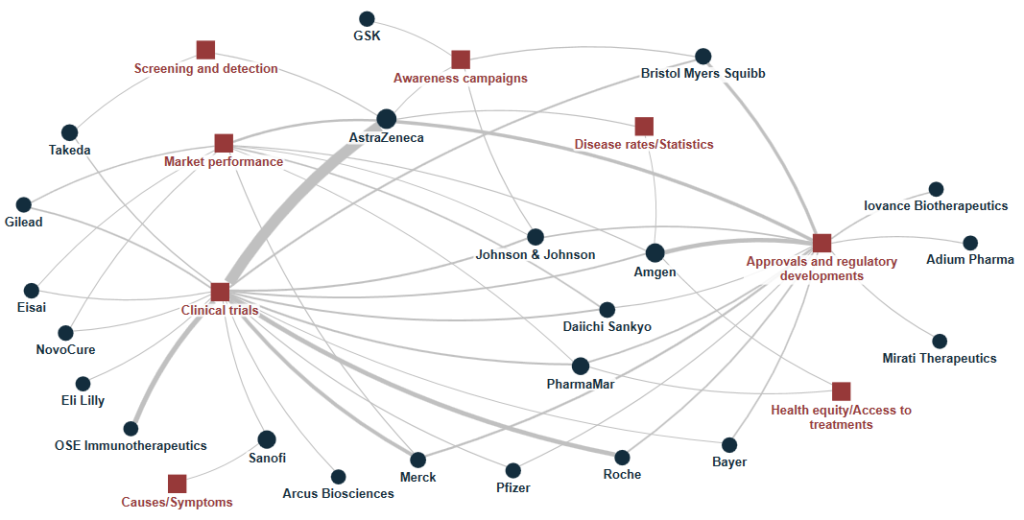

A few pharma companies have engaged with this topic. Our mapping analysis of 2,710 articles on lung cancer in English, German, Italian, French and Spanish showed that the majority focused their PR efforts on clinical trials and regulatory approvals.

This is illustrated on the map below, which shows the links between the topics in the media debate (represented by squares) and the companies (represented by circles).

Notable exceptions were AstraZeneca, which launched a statewide effort to increase annual screenings in parts of the US, and Roche, which provided tests for non-small cell cancers to thousands NHS patients in the UK.

2. Engage with influential patients to educate on causes

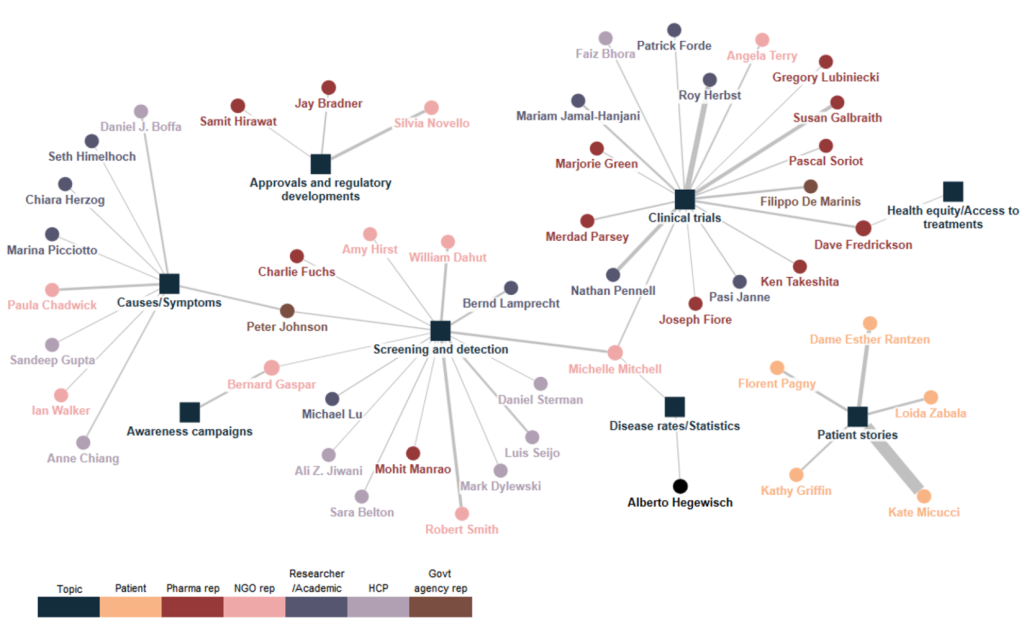

Our mapping analysis found that some of the most influential spokespeople were patients like actress Kate Micucci and comedian Kathy Griffin – both of whom never smoked.

Engaging with key opinion leaders (KOLs) and influencers can effectively raise public awareness that lung cancer can strike people who have never smoked, which in turn can challenge the “smoking-induced” brand attribute and shift blame away from patients.

A key message should be that while there is no disputing the link between lung cancer and smoking, the proportion of non-smokers diagnosed with lung cancer– especially women, of whom over 50% are non-smokers – is increasing due to other risks such as environmental exposures and air pollution, so screening is important for everyone at risk.

3. Change the narrative around smoking addiction

As we saw, smoking is linked to personal responsibility, resulting in blame for those diagnosed with lung cancer.

But the goal of anti-smoking campaigns is to promote health, not to blame individuals. The success of these campaigns in reducing smoking rates is something to celebrate and build on. They shouldn’t be used to add to the stigma around lung cancer.

That’s why an essential part of combating the “smoking-induced” brand attribute can be educating the public about the powerful addictive nature of tobacco.

A number of influencers in the debate around causes (look again at the map above), like Paula Chadwick, chief executive of charity Roy Castle Lung Cancer Foundation and Marina Picciotto, a professor of psychiatry, neuroscience and pharmacology at Yale University, have been quoted in the media expressing such sentiments.

For instance, Marina Picciotto was quoted in a number of media stories as saying that smoking is not just a bad habit, “it’s not something that just anybody can stop doing because they have willpower”.

Collaborating with such key opinion leaders can be a good way to spread the message that smoking is actually a powerful addiction that is very hard to quit, and cancer is a disease, not a punishment.