Why do science communications so often fail to achieve their objectives? Earlier this year the World Health Organisation (WHO) hired public relations firm Hill+Knowlton Strategies to develop a communications programme in the context of the intense criticism levelled at the UN’s public health body for its approach to the global Covid-19 crisis.

In a filing under the Foreign Agents Registration Act, H+K stated: “It has never been a more critical time to ensure that public health messages are understood and resonate across the world. The WHO is a science and evidence based beacon of such information.”

The problem with science and public health communications, including climate change communications, is that they often rely on the so called information deficit model, which assumes that if we teach people what we think they should know, the learned information will change their attitudes, which on their part will lead to behaviour change. In spite of the intuitive appeal of this approach, it most typically does not work. It only works with particular audiences under certain conditions, hence the failure of so many climate change and public health communications programmes.

The first rule of effective communication: Know Your Audience

In order to develop programmes for strategic communications that seek to effectively change people’s attitudes and behaviours, we need to dig deeper into our audience’s values and beliefs, and their level of involvement in the issue, which is essential in terms of whether they respond to information, how they respond to information, and so is important for us in understanding how to communicate with them.

Based on 36 questions that measure what people believe about climate change, their personal involvement in the issue, how much they care about it, how much they think about it, how personally important it is, etc., the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication developed Global Warming’s Six Americas– an audience segmentation of the American public in terms of their values and beliefs about climate change. According to this study, the American public can be divided into six segments as follows:

It is interesting to note that 51% of the US population falls into the top two segments, the Alarmed and Concerned, as opposed to only 21% in the least concerned segments.

In terms of issue involvement, as can be seen in the following chart, the Alarmed and the Dismissive segments are quite firm in their opinions about climate change, i.e. not likely to change them at all but the Cautious and the Disengaged are both above the middle of the scale, i.e. we can change their opinions with a kind of communication that will help them form a real opinion, a real understanding of the issue rather than just being undecided and willing to flip at a moment’s notice.

As a general strategy for social change and getting the society as a whole to move toward action on climate change, we want to move the middle 28 % (Cautious and Disengaged) to the left, i.e. toward the alarmed end of the spectrum. Perhaps, a great part of the Dismissive and Doubtful is never going to change their opinions, but this won’t matter if society changes around them.

Can key opinion leaders effectively communicate climate change?

Key opinion leaders (KOLs) have long been used by public relations firms and inhouse PR teams to create awareness about important social causes or issues with the aim of changing public perceptions and achieving behavioural change.

In order to use KOLs effectively, PR and communications practitioners need to have a solid understanding of how opinion leadership and influence works in practice– both offline and online.

The diffusion of innovations and the multi-step flow of influence are two models that provide practical insights into how KOLs can be used in strategic communications.

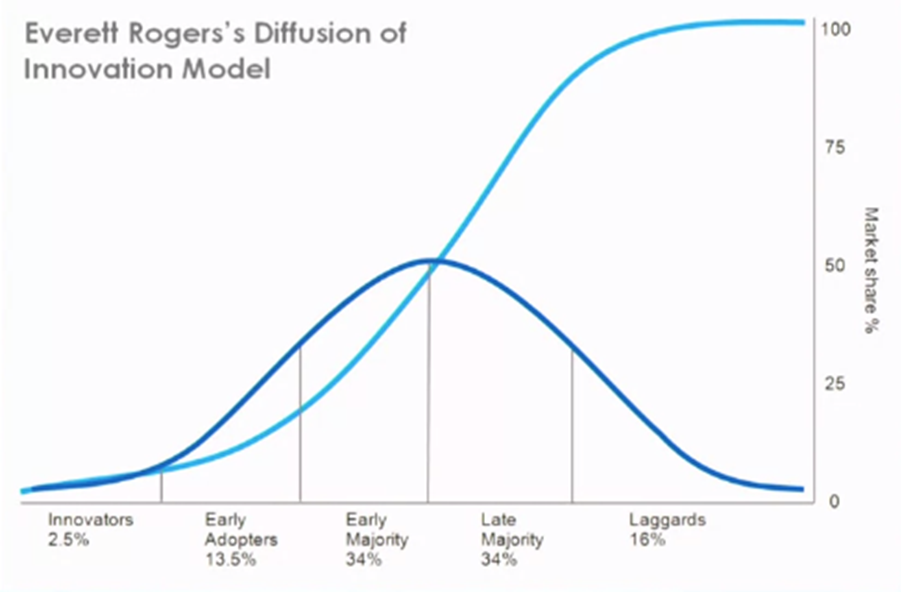

The diffusion of innovations model was developed by Everett Rogers in the 1950s and is often used to understand how change is happening within a system for different types of behaviours, attitudes and beliefs (see the following graph):

At the far end of the graph are the innovators: they are a very small proportion of the public and they tend to be a little bit outside the social system within which they live.

However, they are closely connected to other people who are interested in whatever they are most interested in. So if they are interested in a particular type of technology, they will know other people in distant communities who are also interested in that same kind of technology. The same applies to all sorts of behaviours that are new, e.g. in fashion, hairstyles, health and wellness, etc.

The innovators are paying attention to what is novel and new, and they tend to get their information from the mass media.

The people that often come in contact with the innovators are the early adopters. They represent 13.5 % of the population and have wide social networks. They also tend to be quite respected.

The early majority are looking to the early adopters and follow what they are doing, so they are quite deliberate in their changes.

The late majority are a bit slower to pick up on the change, and the laggards are people who are very traditional in their beliefs and they are the last ones to adopt, if at all.

It is important to note that by ‘adoptions’, we do not mean only adopting a practice or a technology, but also adopting a belief. In the context of climate change, for example, this can apply to recognising that global warming is increasing and that we need to adapt to it.

The first people who adopt an innovation are those using more mass media. At first, there is not much communication inter-personally about the change but over time more and more people are adopting as a result of interpersonal communication.

So the early adopters get the information from mediated communication and the later adopters are more likely to receive it from interpersonal communication. This model of a two-step flow of communication was developed in the 1950s by Paul Lazarsfeld and Elihu Katz, and although it is an oversimplification of reality, it presents a useful starting point for describing how mass media and social influence interact: there is a two step-flow of information from the media to opinion leaders, and then form opinion leaders to the rest of the public.

It follows from these models that climate change KOLs are the innovators and mostly the early adopters. Furthermore, it was assessed by the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication that the Alarmed segment in the Six Americas segmentation has the highest opinion leadership potential.

In conclusion, climate change communicators can reach less engaged audiences through the opinion leadership of the Alarmed innovators and early adopters, as the Alarmed are willing to attend closely to information that less engaged audiences are not interested in.

The main problem with opinion leadership and influencer campaigns, however, is that they take a PR view of influence and reduce its measurement to the simple fact of being potentially listened to, or having an audience, i.e. they ignore the context of the discussions or mentions and often struggle to distinguish the sheer volume of production, or the size of a potential audience, from the actual degree of influence relating to a conversation on a specific topic.

Opinion leadership campaigns are thus rarely tailored to the issue at hand, i.e. KOLs are not selected strategically to overcome the barriers to reaching the target audience via communications, which is the main advantage of using key opinion leaders and influencers.

Influencer personas: the key to successful influencer campaigns

The effective use of KOLs in strategic communications requires the identification of influencer personas (KOL roles) that will best communicate our message to the target audience.

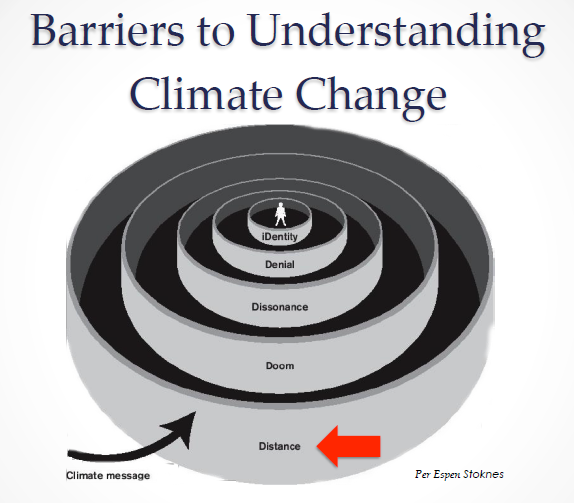

In climate communications, these are the influencers that can help us overcome the target audience’s barriers to understating climate change, as defined by Norwegian psychologist Per Espen Stoknes and shown in the following picture:

Barrier 1: Distance

The negative effects of climate change can often seem distant. The targets are far in the future, distant in space, like glaciers, polar bears, or coral reefs; or distant from some people’s daily lives, like the disproportionate effect of climate on poor people.

Appropriate KOLs: Activists and Journalists/Bloggers

Activists can be used to bring climate impacts close to home and journalists/bloggers can be used to connect climate to issues that matter to our audience.

Barrier 2: Doom

Stoknes noted that according to a study by the Oxford Institute of Journalism, “more than 80% of all climate news had employed the disaster frame.” Overusing the disaster frame can contribute to feelings of hopelessness and despondency that disengage people from climate news.

Appropriate KOLs: Consultants/Business Leaders and Academics

Consultants and academics can be used to emphasise solutions and benefits.

Barrier 3: Dissonance

Cognitive dissonance is a psychological term for the internal conflict one experiences when confronted with new information that clashes with their current experience or world view. People feel a dissonance between their actions and the impact of their action, and respond to their guilt by dismissing the facts of climate change. For example, “I know it doesn’t help climate change to drive a car that uses gasoline, but my neighbour has a much bigger car, so I don’t feel too bad.”

Appropriate KOLs: Celebrities and Politicians

Celebrities and politicians can be used to appeal to group identity and channel the power of social norms.

Barrier 4: Denial

Climate change challenges our core belief that the world is a just, orderly and stable place, so people deny the reality of climate change to defend the status quo.

Appropriate KOLs: Academics

Academics can be used to help people understand different sources of doubt.

Barrier 5: Identity

If taking action on climate conflicts with a pre-existing identity that someone holds, they are more likely to reject climate action than go against their identity. For example, most calls to climate action are done in a way that include a larger government and more intervention and regulation. For someone who identifies as conservative, these may conflict with their identity that values smaller government. In this case, they are likely to employ “confirmation bias,” or filter out news that conflicts with their values or sense of self-identity.

Appropriate KOLs: Ordinary people/Micro-influencers

According to Stoknes, climate communications can benefit from more personal, non-polarizing stories that focus on a positive future. These stories start from imagining what a better, lower emissions society looks like, and celebrating the stories of people that are living that story. By telling these stories, micro-influencers (the Alarmed) can help others see how their identity fits into a future that is acting on climate change.

The best strategy for communicating climate change is to employ a multi-pronged approach to influencing the public by using one type of message that is going to reach through the media to large numbers of people, but then a second strategy will be to use KOLs and influencers that can help PR and communications professionals overcome the target audience’s barriers to understanding climate change, as described above.

Download our 10-page analysis report to learn how we use Commetric’s proprietary influencer mapping methodology to identify and rank KOLs and influencers on social media around climate change.

Great article. I believe to generate actinability one additional step is required. Define action points (with demonstration of impact) for the concerned 51% And make it easier for them to act on those. Eg. For an action point recycling waste, define measurability of Action if followed by 100% population for 1 year. And set up a recycle system so that those who want to recycle are not stranded with no place to dump their waste for recycling.