While the study of crisis management within public relations has emerged with industrial and environmental accidents, the practice quickly evolved to incorporate online cataclysms as one of its main points of concern, as the increasing empowerment of stakeholder groups in today’s hyper-connected economy has led researchers to speak about Internet Crisis Potential (ICP).

This potential is naturally most acute on social media, where the volume of public backlash could start gaining momentum like a boulder down a mountain, leading to serious reputational hazards for a brand and for a whole industry. With this in mind, the most attentive companies constantly monitor conversations via social media listening.

The most severe social media crises happen because of outrage cascades — outbursts of moral judgment which start to drive the conversation around brands, their products and their corporate messages. The virality of moral judgements is facilitated by the fact that most of the content on social media feeds and timelines is sorted according to its likelihood to generate engagement.

A recent NYU research found a pattern in viral posts: the presence of morally charged and strong emotional words in messages increased their diffusion by a factor of 20% for each additional word. This content acts as a trigger for emotional reactions and tends to divide users into two opposing camps. Such polarisation guarantees engagement: users who strongly agree or strongly disagree with a certain message are more likely to comment on it or share it.

Morality equals virality

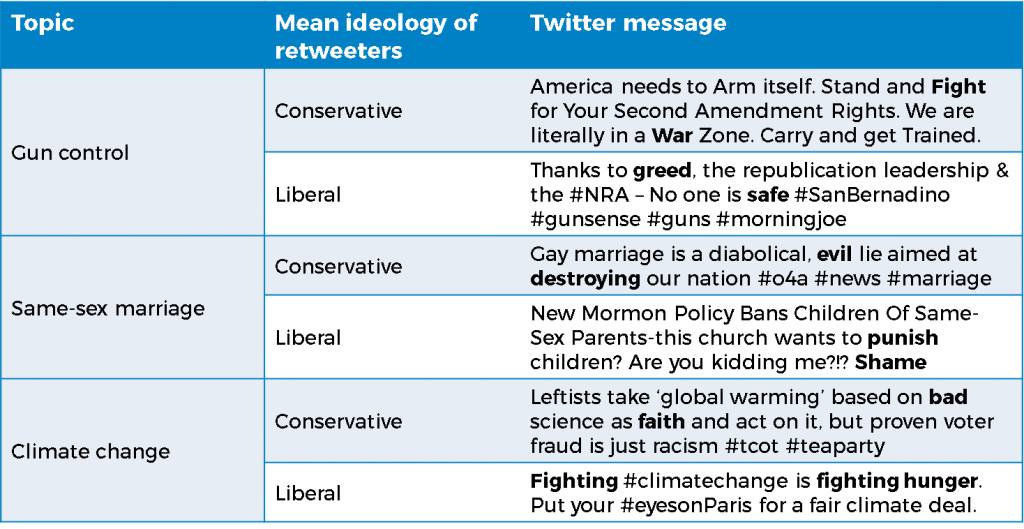

The emotional expression of strong moral views plays a key role in the spread of messages in online social networks – a process called “moral contagion”. The table below presents some examples of tweets that were retweeted largely by two main opposing groups – liberals or conservatives – in conversations around three polarising issues: gun control, same-sex marriage and climate change. Morally charged emotional words are in bold:

In addition, the study found that moral contagion is restricted to group membership: the diffusion of messages was increased more strongly within liberal and conservative networks, and less strongly between them.

The quick diffusion of morally charged messages could also explain how brands end up in social media crises. The most common crisis occurs when users, typically from liberal social networks, deem certain product or corporate message “offensive” or “inappropriate” and they use strong emotional words to condemn the brand.

The crises in social media often serve as coverage drivers in traditional media – an increasing number of outlets report on heated discussions on Twitter, Facebook or Instagram, so a debate on social media quickly turns into a debate on traditional media. Articles are usually being extensively shared throughout social media, perpetuating the discussion and creating a direct correlation between the volume of traditional media coverage and the level of social media engagement.

Recent crises

So a good way of finding the brands experiencing the toughest social media hurdles would be to analyse traditional media conversations.

We studied the discussion around social media crises from October 2018 to April 2019 in the top-tier English-language publications, such as the BBC, Reuters, the New York Times, CNN, Bloomberg and so on, and found the most widely discussed crises:

It’s interesting to note that the brands facing the largest social media crises of late are predominantly from the fashion and food industries. This could be explained by the supposition that fashion and food items are often taken to be markers of cultural and social identity, and thus are susceptible to be perceived as controversial across social networks. For instance, both the fashion and food sectors often draw inspiration from other cultures’ traditions, which has recently given rise to accusations of “cultural appropriation”.

The fact that fashion brands came out on top in our sample could be explained by taking into account the fashion industry’s increasingly controversial presence in the media – apart from cultural appropriation, big fashion brands have faced allegations relating to sexism, racism, harassment, environmental harm, exploitation of workers and so on.

For more insights into fashion’s environmental impact, read our analysis: Sustainable Fashion: Bringing Green into Vogue.

Fashion has also been a central industry in the extensively covered #MeToo movement and has played a major role in ongoing media discussions around gender and identity. Since such issues naturally polarise social media users, brands which are dealing with products directly related to them are regularly caught up in fierce debates.

Some brands have even used this to their advantage – for example, Procter & Gamble’s Gillette focused its latest ad on the #MeToo movement, bullying and “toxic” masculinity, sparking an intense discussion and securing more than 2 million views in just 48 hours. We’ve excluded Gillette from the sample in our current study namely because it encouraged debates intentionally and it didn’t pull its ad, unlike all the brands experiencing social media crises.

To learn all about Gillette’s strategy, take a look at our analysis: Gillette Ad Controversy: Social Media Insights.

An Italian affair

The most widely covered social media backlash in our sample was centred around Dolce & Gabbana and its advertising campaign in China which was declared “racist”. The ads, which were intended to spark interest in a Shanghai fashion show, featured a Chinese woman struggling to eat spaghetti and pizza with chopsticks.

The racism allegations were fostered by the circulation of screenshots of a private Instagram conversation, in which Stefano Gabbana makes a reference to “China Ignorant Dirty Smelling Mafia” and describes the country with a smiling poo emoji. The company said the designer’s account had been hacked.

The debate originated on Chinese platform Weibo but quickly moved to Twitter where it ultimately escalated. Dolce & Gabbana had to cancel its Shanghai show after dozens of celebrities pulled out.

Analysing the Twitter conversation around the brand, we found that messages relating to the controversy had a significant reach, which contributed to the large volume of traditional media coverage:

Applying NYU’s findings, we could attribute the high level of engagement around Dolce & Gabbana to the great number of morally charged emotional tweets. Many of the most often retweeted messages called the ad “racist” or “condescending”, while others called Stefano Gabbana “disgusting”.

A number of users pointed out that Asians invented pizza (vegetable pancakes) and noodles (spaghetti), making it “ridiculous” to show an Asian woman confused by these meals. Some even suggested that the ads are emblematic of the white West’s orientalist perception of China, violent fetishising portrayals of East Asian women and the white neo-colonial desire to exploit China’s wealth.

The Twitter discussion was also amplified by users sharing pieces of the extensive coverage provided by major media outlets. Retweets of articles and other people’s opinions constituted most of the conversation. The top trending article on Dolce & Gabbana across all social media platforms was published in South China Morning Post under the title “Dolce & Gabbana founders ask Chinese people for forgiveness after ‘racist outburst’” and had 31.9K engagements.

The backlash was amplified by Chinese film star Zhang Ziyi, who said she and her team “will not buy or use” any Dolce & Gabbana product, while singer Wang Junkai said he had terminated an agreement to be the brand’s ambassador. Online retailers such as Alibaba’s TMall and JD.com Inc. removed Dolce & Gabbana’s products from their Chinese sites, and Lane Crawford and other high-end luxury stores pulled the brand’s wares.

Influential fashion outlets like Vogue China featured no Dolce & Gabanna ads, and at the Golden Globes and the Oscars, no A-list celebrities wore the label. These moves were welcomed by many Twitter users, who claimed that the brand deserves the boycott and that China has taught a lesson to “a racist establishment”. The extent of the backlash could be illustrated by a sentiment analysis:

Fashion brands have long strived to provoke with controversial marketing campaigns, especially in China, the country expected to drive most of the industry’s growth. Chinese consumers account for around a third of global purchases of luxury products, according to Bain & Co. Dolce & Gabanna might lose their share in an important market, where rivals such as Louis Vuitton and Gucci are vying to expand.

The brand’s crisis communications were not successful and even worsened its image. Domenico Dolce and Stefano Gabanna tried to get personal and issued a video apology to Chinese consumers on social media, saying that they hope their misunderstanding of Chinese culture can be forgiven. They also posted “dui bu qi,” which means “I’m sorry” in Chinese. Social media users largely interpreted this as insincere, with some even saying that the designers’ body language gave them away, while others asserted that the brand is only apologising for the money it will lose.

Joakim Lundquist, CEO of Italian communications consultancy Lundquist, told Forbes: “The Dolce Gabbana crisis should be seen as a wake-up call for companies in the fashion industry. Scandals like this confirm our research findings that fashion and luxury companies can no longer afford to ignore stakeholder expectations for transparency, openness, accountability and dialogue.”

Fashionable excuses

Gucci handled its own crisis more convincingly after its woollen “balaclava jumper” was criticised on social media for “resembling blackface”. Users said that this comes as part of the fashion industry’s “continuous cycle of disrespect” and that gigantic brands like Gucci create offensive “fashion”, quickly apologise, and then state “We did not know”. Others remarked that what made it worse was that the controversy was taking place during Black History Month.

Apart from apologising in a tweet, the brand announced that its first step towards regaining trust would be the Gucci Changemakers program with Harlem designer Dapper Dan. The initiative aims to “support industry change and to foster unity through community action” with the help of the $5 million Gucci Changemakers Fund, which will be used to build “strong connections and opportunities within the African-American community and communities of color at-large, while bringing positive change and inspiring solutions for a better future”.

Gucci also introduced its Changemakers Scholarship program to support students interested in working in the fashion industry with a $20,000 grant to help fund their education over the course of four years. The last part of the brand’s initiative was the Gucci Changemakers Volunteering program, which “empowers all 18,000 Gucci employees worldwide to dedicate up to 4 paid days off for volunteering activities in their local communities.”

Appropriation continued

Another brand deemed “racist” on social media was H&M for showing a black child modelling a hoodie that says ‘coolest monkey in the jungle.’ Meanwhile, Vogue was accused of cultural appropriation for a shoot showing Kendall Jenner with what was perceived as an “afro”.

Dior was caught up in a crisis over its Cruise 2019 campaign featuring Jennifer Lawrence, which referenced “the escaramuzas-empowered and highly-skilled Mexican horsewomen” as well as Chilean characters from a novel. Many social media users criticised the brand for its decision to cast a white actress in a campaign honouring Mexican heritage.

Burberry, on the other hand, owed its centrality in the media discussion due to the online backlash that followed after the brand showcased a hoodie featuring a noose around the neck at the latest instalment of London Fashion Week. Model Liz Kennedy, who said her concerns about the use of a noose were neglected, wrote on Instagram: “Suicide is not fashion. It is beyond me how you could let a look resembling a noose hanging from a neck out on the runway I had asked to speak to someone about it but the only thing I was told to do was to write a letter.”

Burberry’s hoodie dominated the Twitter discussion around London Fashion Week, with the abundance of negative comments being one of the main reasons for the brand’s decision to remove the jumper from its collection. Twitter users wondered how Burberry even let the hoodie go out to production, saying that it’s an unbelievable blunder. Many said that this was actually a marketing strategy and that such designs are showcased for the free “outrage” coverage.

Others connected the fashion item with Black History Month and asserted that the noose is a symbol of racial terrorism. Some users sharing this sentiment thought that “black outrage” is the new trending marketing tactic because such controversies drive clicks and keep the brand in the news.

All these brands tried to deal with their social media crises by apologising and removing the controversial items from their collections. They also tried to communicate corporate values such as inclusivity, but almost all of these attempts were met with skepticism and sarcasm.

Backlashes around the corner

A great number of Twitter users drew parallels between Dolce & Gabanna’s gaffe and the latest social media crisis in the food industry: Burger King’s New Zealand ad campaign for a new Vietnamese burger which showed western people trying to eat a burger with oversized red chopsticks. The backlash was significantly smaller than Dolce & Gabanna’s, and the story was picked up by fewer news outlets.

Many users noted that no one learned from the Dolce & Gabbana scandal and that the fashion brand had to apologise to “literally all of China” because they ran an ad that basically had this premise. Others were astonished that “someone pitched this, someone okayed it, someone filmed it, and someone showed it to human beings” and that the company didn’t realise that this was “racist” because it didn’t have a diverse board of marketing strategists. One popular tweet said that the only way to process this without getting incredibly angry is to imagine that the chopsticks are regular sized, the burgers are tiny and dim sum style, and the racists are shrunk.

As in Dolce & Gabanna’s case, the diffusion of messages occurred primarily through retweeting:

However, the discussion around Burger King was more balanced: even though positive tweets were less retweeted, there were many users who defended the brand by saying that the ad shouldn’t be perceived as offensive. There were also users who expressed more nuanced opinions with a neutral sentiment, saying that the brand just tried to create a humorous ad.

Those defending the brand tweeted that those offended by the ad have to live “a sad, sad life” and that the word “racist” has lost so much meaning that it completely ignores the real racism going on around our world. Others were harsher, saying that they live in a dumb and sensitive era where there are “snowflakes” who simply have to have something to whine about and always find something to be outraged over.

Like the largest social media crisis in the fashion industry, the largest crisis in the food industry emerged by a brand trying to establish itself in a foreign market. Burger King responded by deleting the ad and by issuing a statement saying: “The ad in question is insensitive and does not reflect our brand values regarding diversity and inclusion.”

A need for new strategies

Burger King’s apology, just like the apologies by the other companies in our sample, was taken with a pinch of salt by social media users. The ones attacking the brand felt that it was insincere when apologising and that it pulled the ad just because they had no other choice. On the other hand, the ones defending the brand said that it caved to the pressure and wanted to satisfy overly sensitive consumers.

The main problem was that most brands used the same crisis communication strategy for both traditional and social media. This strategy included formal expressions of regrets and carefully worded explanations of corporate values, which were by nature aimed at professional journalists and fell apart when communicated to social media networks. The formal corporate tone of such messages alienated many users and deepened the crises.

In general, apologies tend to trigger negative reactions from both the liberal- and conservative-minded users who play the most active parts in social media discussions. Liberal users usually think brands are being insincere, while conservatives typically say that the sensitivity around these issues has gone too far.

These problems are rooted in the fact that most of the crisis communication theories are based on traditional media and researchers have traditionally tried to adapt them to social media. A popular starting point is the three-stage process developed by crisis management scholar Timothy Coombs, which consists of a pre-crisis stage (detection, prevention attempts and crisis preparation), a crisis stage (crisis recognition and crisis containment) and a post-crisis stage (evaluation).

However, these models don’t take into account social media’s shift in power from formal to informal communications, the growing influence of stakeholders and the fact that outbursts of moral judgment often drive the conversation around brands, their products and their corporate messages.

Reputational risks could easily be mitigated if brands outsource their messaging to key opinion leaders who can generate organic audience engagement within a social media network or around a certain topic. Instead of engaging in push advertising as part of their expansion in foreign markets, Dolce & Gabanna and Burger King could have promoted their products by employing influencers familiar with the subtleties of the local consumer landscape.

The two largest social media crises in the fashion and the food industry underlined the many reputational dangers in the way of brands trying to enter a demographic whose idiosyncrasies and sensibilities are still unknown to them. As conveying corporate messages in the right way is becoming more and more challenging in today’s increasingly hyper-connected engagement-driven economy, brands should rely more on key opinion leaders to navigate discussions.

For more on this topic, read about the role of influencer mapping in reputation management.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks