“We don’t have the strongest reputation on privacy right now, to put it lightly”, Mark Zuckerberg said at F8, Facebook‘s conference at the end of April. “But I’m committed to doing this well and starting a new chapter for our product.”

This new chapter is supposed to be a transition of emphasis from the News Feed to a “privacy-focused communications platform” which brings the company’s messaging products to the fore and unifies them around six principles: private interactions, encryption, reduced permanence, safety, secure data storage and interoperability between Facebook-owned platforms. The new corporate vision was encapsulated by Zuckerberg’s solemn announcement: “The future is private“.

This new narrative and apparent shift of business model aim to pull Facebook away from the edge of the reputational precipice where it’s been standing for the last three years or so. During that time, the company made global headlines for a string of failures, including the Cambridge Analytica scandal, the 2016 election meddling, the “fake news” phenomenon, the sharing of sensitive data to third-parties and the hacking of millions of accounts. As a former Facebook employee told WIRED, the firm’s PR department has become “a crisis communications shop”.

Reputational bottom

The ongoing series of crises made the social media giant fall to the bottom of Reputation Institute’s U.S. RepTrak. The only company with a lower ranking was the Trump Organisation, while the company above Facebook was Philip Morris, a symbol of the vilified tobacco industry. Compared to the benchmarks of other behemoths like Netflix, LinkedIn, Microsoft, Google, Facebook was the only tech business in the weak range.

The company experienced significant decreases in metrics such as citizenship, leadership, governance, data privacy pulse scores and overall reputation equity. The most vulnerable areas were citizenship and governance, the dimensions aligning with perceptions of ethics, morality and social responsibility.

Facebook was also the worst performing company in the 2019 Harris Poll Reputation Quotient – it went from No. 51 in 2018 to No. 94. A survey conducted by the company found that 69% of Americans consider the privacy of data a number one priority, while only 15% thought that Facebook does a good job at protecting sensitive information. In addition, only 22% of Americans said that they trust Facebook with their personal information, significantly less than Amazon (49%), Google (41%), Microsoft (40%) and Apple (39%).

Reputation analytics: a new way to measure corporate reputation through the media

Approaches to measuring corporate reputation have traditionally been fraught with conceptual difficulties of what exactly constitutes ‘corporate reputation’, and many models suffer from one-dimensional focus. More robust models, such as the Harris Poll Reputation Quotient (RQ) and the Reputation Institute’s RepTrak, offer multi-dimensionality and attempt to analyse the link between reputation and financial performance, which is hard to prove.

It seems that there is no direct correlation between stock market performance and corporate reputation at least in the short term, as the case of Facebook shows: the company’s share price has not suffered dramatically in line with its reputational decline, and actually tends to recover after crises.

These models rely mainly on survey methods to collect data about the various dimensions of corporate reputation, which makes their administration and application difficult for the purposes of ongoing reputation analysis and management.

A key input into most reputation measurement models is media coverage, looking at how and what the media is covering about the company, which leads us to speak about ‘media reputation’. The media can have a disproportionate impact on a company’s reputation due to the fact that in many industries it is the primary shaper of public knowledge and opinions about companies, especially in cases when the public does not have any direct experience with those companies or the issues surrounding them.

In this regard, we align with Deephouse (2000) proposition that a company’s media reputation can be viewed as a strategic resource, part of the intangible assets of the company, so it should be managed accordingly. Reputation analytics is thus analysing the drivers of corporate reputation as presented in the media.

A major problem with measuring reputation through the media is the reliance on manual processing of media data to identify reputation drivers and their underlying sentiment, which in spite of achieving precision and recall close to 100%, is restricted to smaller samples sizes, usually less than 1,000 articles.

Recent developments in text analytics technologies, particularly natural language processing (NLP) and deep learning, have enabled the design of media reputation measurement models that produce results similar to survey-based methods. We use one such model – our proprietary reputation analytics framework ComVix – to analyse and measure Facebook’s reputation, and compare it with that of three other big tech companies – Google, Amazon and Netflix.

While other media analytics platforms categorise entities or topics, ComVix is capable of disambiguating sentence structure to classify the business events that drive corporate reputation. Using a hybrid between rule-based NLP and machine-learning, we have developed the most granular taxonomy of business events driving corporate reputation to date, achieving precision and recall of above 90%.

A key component of our model is uncovering the sentiment at scale, i.e. uncovering the sentiment associated with each individual construct (e.g. company) within each article. Uncovering sentiment at scale and hence interpreting the drivers of reputation, requires allocating sentiment with individual constructs, which most media analytics platforms doing automated sentiment analysis fail to do.

Our reputation analytics platform ComVix is able to automatically track almost 500 news-reported business events driving corporate reputation, categorized into 18 overall reputation drivers as presented below:

Finally, we base our quantitative measure of corporate reputation on Net Promoter Score (NPS), calculated as the difference between positive mentions and negative mentions per driver, to arrive at ComVix Reputation Index (CRI).

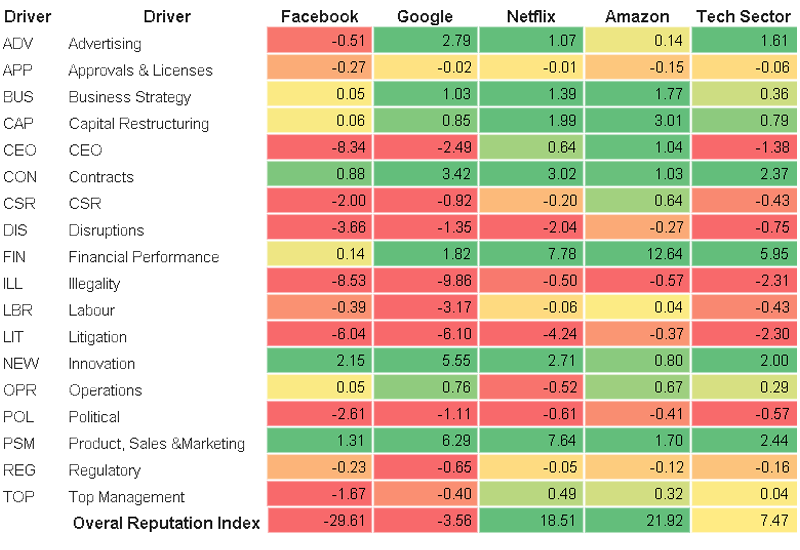

Just like NPS, CRI ranges between -100 and 100, with positive results generally deemed good, and CRI of +50 deemed excellent. The heat map below presents the CRI for Facebook, Google, Netflix and Amazon, as well as for the entire Technology Sector, encompassing 889 large cap companies listed on NASDAQ. The analysis is based on 2.7 million articles for the period 1st April 2017-31st March 2019.

Illegality: Facebook’s strongest negative reputation driver

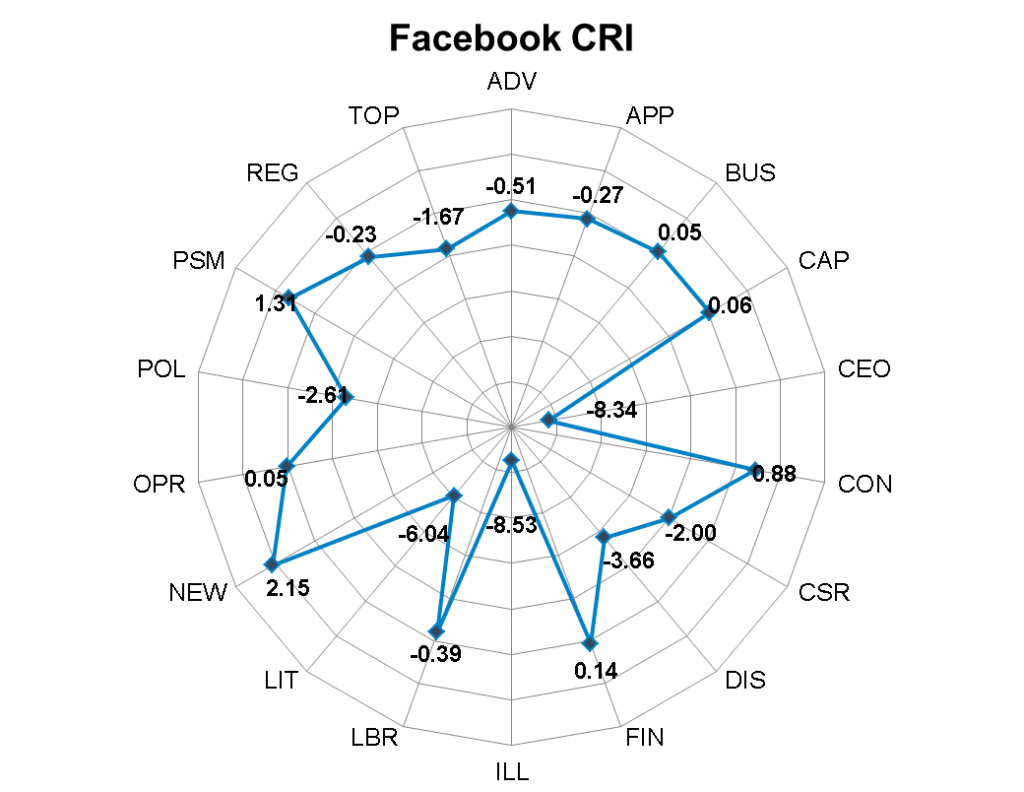

Unsurprisingly, Facebook`s reputation index is pretty negativе, with an overall CRI standing at -29.61.

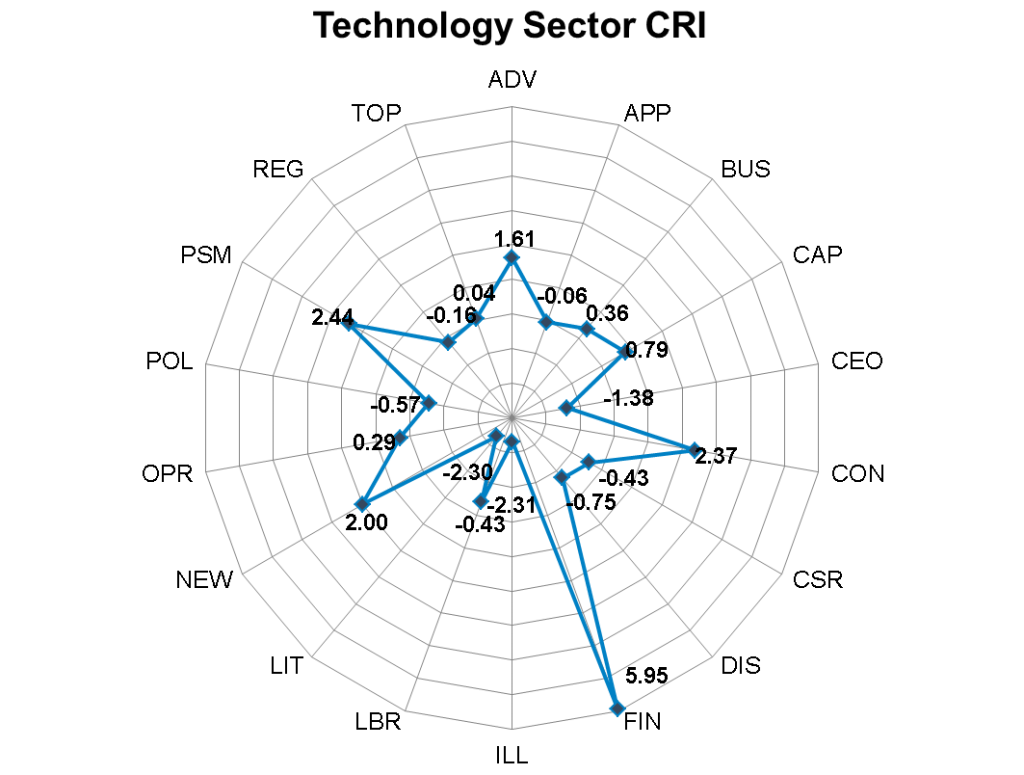

Facebook’s CRI results are presented in the radar chart below :

The strongest driver behind this score was Illegality or illegal actions (ILL), which stood at -8.53. The negative sentiment was a result particularly of the company being accused of wrongdoing, which has led to much more negative coverage than when it was actually found guilty and fined by regulators.

Facebook has maintained a regular presence in the news cycle due to a large number of various accusations coming from policy makers, regulators, the media and the public. The latest instances included the Observer alleging that there was an executive-level cover-up of Cambridge Analytica’s scandal and Brussels saying that the company took a “patchy, opaque, and self-selecting” approach to tackle disinformation.

When it comes to disinformation, the company was recently in the spotlight for its role in spreading anti-vaccination content. The Daily Beast reported that more than 150 anti-vaccine ads had been bought on Facebook and were viewed at least 1.6 million times and after The Guardian found that anti-vaccination information often ranked higher than accurate information.

After Cambridge Analytica, Facebook regularly gets in the media spotlight around major elections. Most recently, a report by online activist group Avaaz found that far-right and anti-EU groups are using Facebook to spread false content relating to the European elections. Such content amassed followings several times larger than following of the actual far-right groups.

Avaaz accused Facebook of allowing far too much suspicious activity and malicious content to spread, although COO Sheryl Sandberg had said that the company is blocking more than 1 million fake accounts every day.

The report came after a study conducted for the Oxford Internet Institute’s (OII) Computational Propaganda Project, which found that sources of disinformation on Facebook can still hugely outperform stories by professional journalists in terms of shares, likes and comments.

Avaaz reported more than 500 suspicious pages and groups to Facebook, with the company acting against 77 of them, in addition to removing more than 200 accounts. The misinformation spread by far-right was viewed 533 million times over the past three months.

A Facebook spokesperson issued a statement saying that the company is “focused on protecting the integrity of elections across the European Union and around the world”. But most media outlets agree that the social media giant still hasn’t found a way to keep misleading information from spreading in the first place.

The CEO as a key driver of corporate reputation

Mark Zuckerberg is often the focal point of any scandal and is naturally the first person held responsible for all of the company’s missteps. As we can see from the chart, his actions were the second strongest negative reputation driver.

It’s interesting to note that the bulk of the negative coverage was caused not so much by the scandals themselves but rather by the CEO’s crisis communications approach. This was reflected in CEO’s CRI score, which stood at -8.34, just a few behind the ILL score.

Zuckerberg has been talking and apologising about privacy since 2003. Whenever he issues a statement addressing a certain failure, the media is quick to scrutinise his words and often criticise him for being insincere or unspecific. A common criticism is that he fails to fess up to all the facts at the outset of a crisis and that he generally lacks transparency and seems increasingly out of touch with Facebook users.

He also often fails to follow the standard crisis communications playbook by being too slow to react and to take immediate action without signs of hesitation, which is usually perceived as responsible behaviour, as empirical research has shown.

When it comes to dealing with a corporate crisis, the gold standard was set by pharma company Johnson & Johnson in 1982 when it recalled its pain relief product Tylenol and implemented a decisive response strategy which included a forthright media campaign.

Johnson & Johnson was praised by consumers, regulators and the media for acting quickly and openly, and for communicating the measures it took. The brand’s reputation was even boosted by the manner in which it managed the crisis because the company showed that it prioritised consumer well-being even though the recall cost millions.

Acting immediately, apologising, being transparent and being accountable has since been the tenets of crisis communications strategies, and companies from General Motors to Pepsi have assiduously followed this template.

But when the New York Times and the Guardian broke the Cambridge Analytica story, Facebook didn’t seem too eager to implement such measures. Instead, Zuckerberg’s statements and subsequent blog posts framed the misuse of user data as the fault of a few rogue actors, without acknowledging that Facebook’s own problems. In addition, the company’s lawyers sent bullying letters to the New York Times and the Guardian, which accelerated the crisis.

When Zuckerberg adopted an apologetic tone and stressed the need to do a better job, he said: “We have a responsibility to protect your data, and if we can’t then we don’t deserve to serve you.” But this statement seemed quite out of place when in September 2018 another security breach exposed the data of 50 million users.

Last year, Zuckerberg gave a 10-hour testimony to Congress, which was perceived to be more about political theatre than about political regulation. Although some crisis communications experts agreed that he did a good job, many media outlets criticised him for not sharing enough information about his company’s business practices.

At the beginning of this year, Zuckerberg addressed Facebook’s critics from the pages of the Wall Street Journal but instead of taking complete responsibility, he asserted that the company was misunderstood. It was an example of the CEO’s oft-used tactic to argue on semantic grounds, saying that his firm doesn’t “sell” its users’ data but simply charges businesses a fee to access it for advertising purposes.

Other reputation drivers

Another prominent reputation driver was Litigation (LIT), which stood at -6.04 and most often referred to the company being sued. A recent instance was the Washington, D.C., attorney general saying he will sue Facebook over a violation of the District’s Consumer Protection Procedures Act, alleging that the firm allowed users to download an app developed by Cambridge Analytica which improperly got access to private information.

Meanwhile, Facebook expects to be fined up to $5 billion by the Federal Trade Commission for privacy failings, with the record penalty being interpreted by the media as a sign that the United States wouldn’t hesitate to punish big tech

Disruptions (DIS), which was -3.66, has also been a cause for media concerns. One of the latest instances was when WhatsApp was hacked, exposing a “serious security vulnerability”. Facebook didn’t address the issue or notified users more than 12 hours after the Financial Times broke the story – a problem which many media outlets compared to Facebook’s bad response to the Cambridge Analytica scandal, saying that the company is still slow to talk to its users about privacy.

This has made Facebook lag behind Amazon, Netflix and Google:

The only relatively strong positive drivers have been Innovation (NEW), which was +2.15, and Products, Sales and Marketing (PSM), which was +1.31. While Facebook has been dealing with crisis after crisis, it has done a good job with promoting its new products and features, such as the virtual reality Oculus GO, the new feature that lets users watch video while chatting with friends, and the new group video option on Instagram and WhatsApp.

Image vs reputation

According to the Reputation Institute, one of the main problems for Facebook was that it has tried to protect its image rather than its reputation.

Although there are no fixed definitions of both “image” and “reputation”, scholars generally agree that corporate image is about the short-term evaluation of an organisation’s communication, while corporate reputation is the long-term impression and social evaluation that specific publics have.

In other words, corporate image is the immediate mental picture that audiences have of an organisation, which can be crafted through well-conceived communication programmes. On the other hand, corporate reputation is predicated on a value judgement about the company’s attributes and is based on consistent performance, reinforced by effective communication.

Facebook’s mistake between the two was highlighted by a New York Times investigation which found that the company had tried to downplay its role in the 2016 U.S. presidential election affairs. Its communications approach was rather sketchy: it hired PR firm Definers Public Relations, which wrote critical articles about Google and Apple and pushed the idea that George Soros was the mastermind behind a growing community of Facebook critics.

After Elliot Schrage, Facebook’s outgoing head of public policy, published a blog post on this topic, COO Sheryl Sandberg revealed that she had known about Definers Public Relations’ activity and herself directed Facebook’s communications team to probe the financial ties of George Soros. It was also revealed that Sandberg was angry with Facebook’s former chief security officer Alex Stamos for investigating the Russia allegations without her permission, which was largely interpreted by the media as efforts to avoid accountability.

In the meantime, the company’s share price has not suffered dramatically and actually tends to recover after crises, and not that many users are taking drastic measures such as deleting their accounts – an example of how a company can have a strong brand and a bad reputation at the same time.

This takes us back to the old PR proverb that “branding can make you relevant, while reputation can make you credible”. And it seems like Facebook is indeed relevant – in W2O’s latest ranking of Fortune 100 companies’ relevance, the social media giant was ranked No. 1 for the second year in a row because of its consumers’ online behaviour, employee chatter, investor activity and CEO dynamism as a leader.

“Facebook has a tremendous amount of problems. However, to their stakeholders — to the people who use them, articulate who they are and convey their narrative — they are as relevant as ever,” W2O principal Gary Grates said.

People moves

Changes in top management also seem to have a negative effect on Facebook’s reputation with a TOP score of -1.67.

We are yet to see how Facebook will deal with its reputational woes after undergoing a major executive reorganisation of its communications team in the past few months.

In February, the company’s vice president of communications, Caryn Marooney, left the company after eight years. She was replaced by John Pinette, a former Google and Microsoft communications director, while Sir Nick Clegg, former deputy prime minister of the United Kingdom, was hired to lead global policy and communications.

Clegg explained why he is joining the company in a Guardian article, saying that he remains “a stubborn optimist about the progressive potential to society of technological innovation”. His move was subject to many analyses, with journalists pointing out that his political experience will help him when dealing with regulators and that the company didn’t choose someone from the increasingly polarised American political landscape to avoid allegations of bias.

Clegg has already started to shift the company’s tone towards more open and conciliatory messaging, admitting that in a bad place on several fronts and, as the BBC put it, “casting himself as the adult who can make this young company grow up”.

In the meantime, the longest-tenured employee on Facebook’s communications team, Debbie Frost, Facebook’s vice president of international policy and communications, also announced her departure, while Sarah O’Brien, a former communications vice president at Tesla, was hired to be the company’s vice president of executive communications.

Antonio Lucio became Facebook’s chief marketing officer – a job which has been called one of the most challenging leadership positions in Silicon Valley. He joined the company from HP, where he pursued emotion-heavy communications strategies revolving around family values. Chris Cox, Facebook’s chief product officer, said that Lucio “has been outspoken on the need to build authentic global brands with integrity and from places of principle” and that Facebook’s story is at an inflexion point.

At the other end of the spectrum

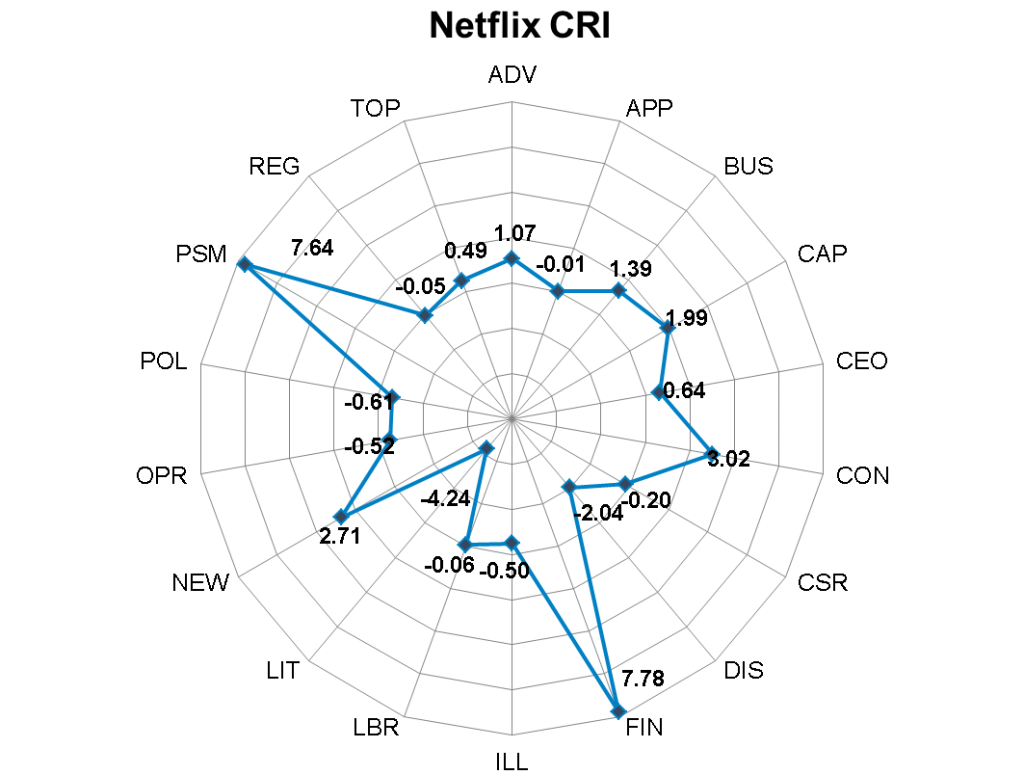

The top company in the Reputation Institute’s U.S. RepTrak 100 was also from the tech sector – Netflix. The streaming video service was the first company to have surged to the number one spot over the course of a single year in the whole history of the RepTrack. The Institute said that it won the top spot by increasing the power of its brand globally, innovating as a content creator, exhibiting corporate responsibility and taking decisive action on important issues.

Apart from Financial Performance (FIN), Netflix’s strongest positive reputation driver was also related to its products (PSM), which was +7.64. Netflix successfully shifted from media repository to a content-creator: apart from hosting classics like The Office and Friends, the company created original shows like Black Mirror, Queer Eye and Stranger Things.

The company was generally praised in the media for firing Kevin Spacey because of the allegations of sexual harassment against him. The affair dominated the news cycle for a long time and became one of the most popular stories in the conversation around the #MeToo movement. Most recently, Netflix became the first major US studio to speak out against the antiabortion laws discussed in Georgia, Alabama and Missouri. The company was perceived as an organisation with strong values which isn’t afraid of taking decisive actions and is prioritising ethics over profit.

Netflix’s most prominent negative reputation driver was Litigation (LIT), which was -4.24. Most recently, the company was sued for $25 million over an episode of ‘Black Mirror’ whose title was similar to a series of novels called “Choose Your Own Adventure”, with the novels’ publishers claiming that Netflix violated its trademark.

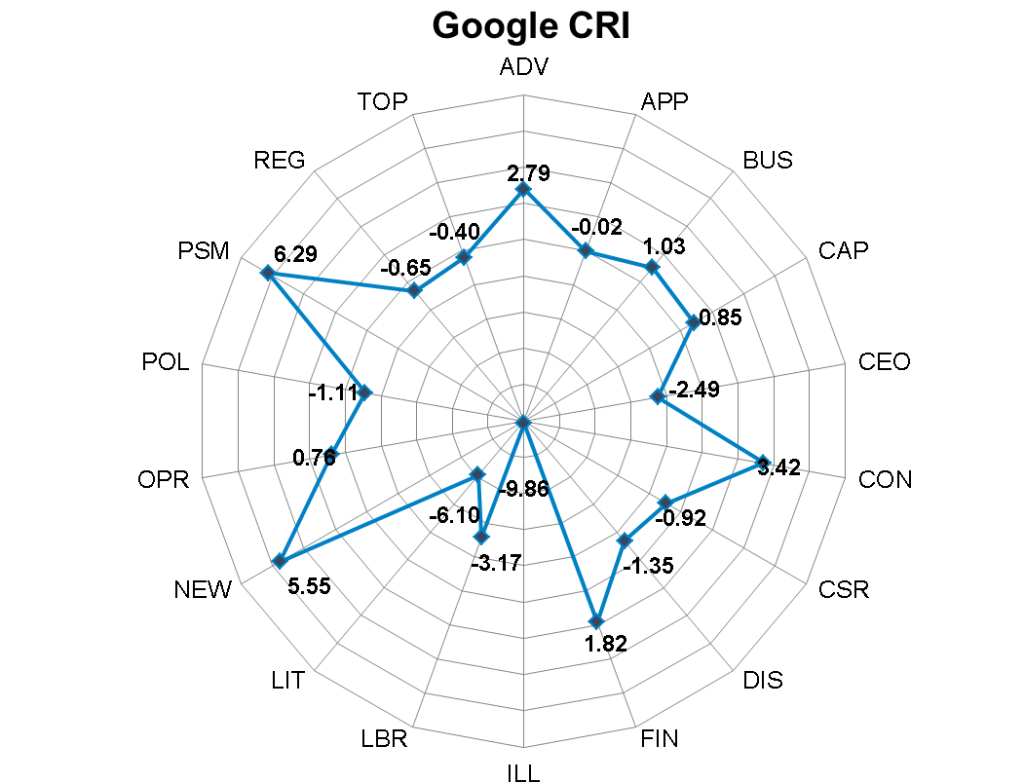

Meanwhile, Litigation (LIT), alongside Illegality (ILL), made another tech giant drop out from the RepTrack’s US 100 for the first time ever. Google experienced some heavy clashes with regulators. But albeit in the negative spectrum, Google’s CRI results are significantly better than Facebook.

Google’s strongest negative reputation driver (ILL: -9.86) primarily revolved around allegations for abuse of market power. The company’s legal troubles deepened two years ago, when the European Commission fined it €2.42 billion for abusing its market dominance.

Following complaints by several rivals, including companies such as Microsoft, Yelp, Trip Advisor, Getty Images, the Commission found that Google had taken advantage of its leading position in the internet search market by promoting its shopping service unfairly: it had been displaying it at the top of the search results, while rival services had appeared on average only on page four.

In 2018, the Commission fined Google €4.34 billion for imposing illegal restrictions on Android device manufacturers, and at the beginning of 2019, it fined the tech company €1.5 billion for further antitrust violations.

Like Zuckerberg, Google CEO Sundar Pichai made privacy the main topic of his company’s 2019 conference, the Google I/O event in Silicon Valley. His keynoted speech, as well as the thoughts on data protection that he shared in an article for the New York Times, were welcomed far more warmly than Zuckerberg’s ideas. As TechCrunch put it, while Zuckerberg was saying “The future is private”, Pichai’s message was “The present is private”.

In the specialised media, Google is generally perceived to be doing a better job than Facebook at protecting users’ data. While Facebook is emphasising privacy to repair its reputation, Google hasn’t waited for its users to demand more privacy but has demonstrated a steady commitment by doing away with using Gmail content to target ads and allowing any developer to request access to emails. It also opened a new hub for privacy engineering in Germany.

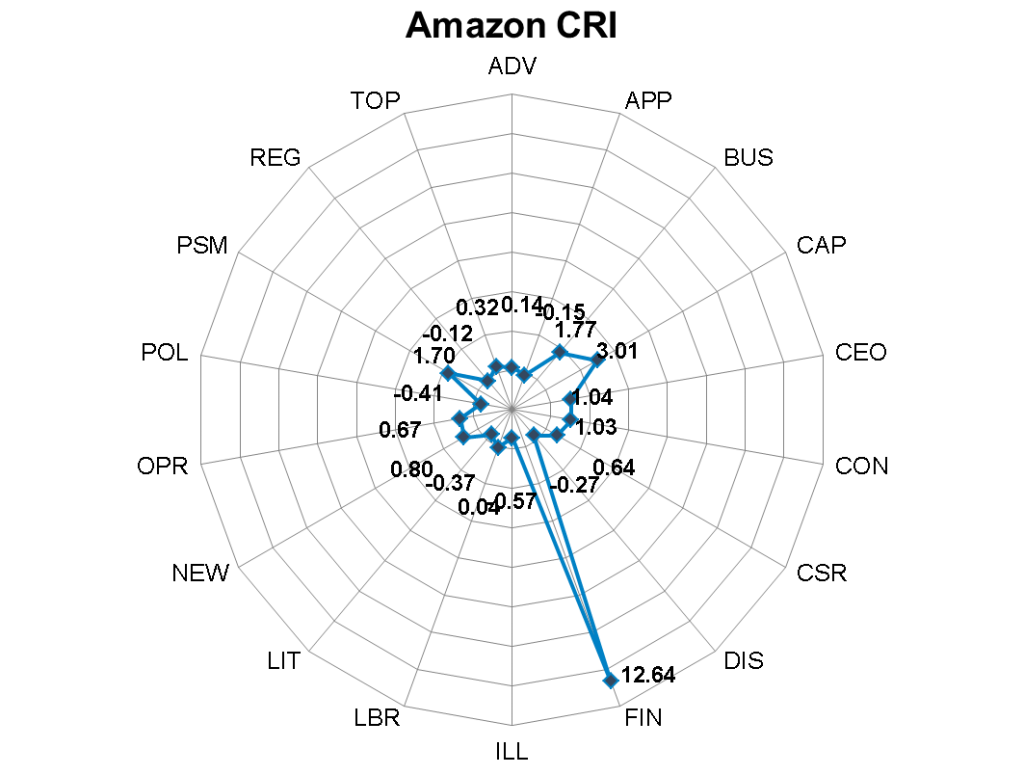

Amazon’s high CRI results were mainly due to the positive media coverage around its financial performance (FIN), capital restructuring (CAP), business strategy (BUS) and products (PSM).

While Facebook has concentrated its efforts internally, Amazon has continued to rely on continuous business diversification – last year alone, it invested billions in more than half a dozen business initiatives.

Perhaps its most often discussed venture was its entry into the healthcare market – in June 2018, Amazon announced it was buying online pharmacy PillPack for $753 million. The company was also often mentioned in relation to its partnership with JPMorgan Chase and Berkshire Hathaway, which aims to reduce healthcare costs for employees, its investment in cancer detection start-up Grail and its plans to transform its virtual assistant smart speaker Amazon Echo into a home healthcare tool.

Amazon was also among the central brands in the media conversation around the 2019 J.P. Morgan Healthcare Conference, the most important annual event in the healthcare sector, in which healthcare’s intersection with tech was a major topic. In this regard, CNBC wrote that Amazon stokes “both excitement and fear”.

As the global healthcare sector is facing huge disruption by tech giants which start competing with traditional players in the market, Amazon is the name which comes up most often in this context, as our analysis showed.

In addition, Amazon has shown interest in autonomous technology by investing in self-driving car start-up Aurora earlier this year, and in sustainable transportation by investing in electric truck start-up Rivian.

CEO Jeff Bezos’ passion for outer space is well-documented and serves for the basis of many futuristic analyses and comparisons with Elon Musk. Most recently, Amazon’s activity in this domain was Project Kuiper, which aims to launch more than 3,000 satellites to provide high-speed internet access across the world.

Tech’s reputational troubles

Consumer concerns about privacy have been around since the dawn of the Internet, and data breaches regularly make headlines around the world. Recent high-profile examples include the cyberattacks against Equifax, Yahoo and Uber.

But Facebook’s troubles were what really made data privacy a central concern for consumers – it became clear that improper handling of sensitive information can lead not only to financial abuse but can also influence global politics and people’s health and well-being.

The risk associated with the way data is used versus the way it’s safeguarded is becoming a priority for an ever-larger group of stakeholders, not just regulators and policy makers. This made Illegality (ILL) and Litigation (LIT) the most sensitive reputation drivers for the tech industry, which otherwise enjoys fairly positive CRI results.

It is no wonder that Ipsos MORI’s Reputation Council, a panel of senior corporate communication professionals, identified cyberattacks as the greatest threat to their company’s reputation. For nearly half of the panellists, data breaches are as harmful to a firm’s good name as poor product quality and staff malpractice.

Indeed, the majority of consumers would not use the services of a company which has been hacked. In a survey commissioned by fraud prevention company Semafone, 86.55% of respondents said that they were “not at all likely” or “not very likely” to enter in a relationship with a company after a data breach involving credit or debit card details. “These figures serve to underline what we should already know – that the reputational damage suffered by companies who fail to protect personal data can translate directly into a loss of business,” said Semafone’s CEO Tim Critchley.

This has put corporate governance (honesty, transparency and ethical behaviour) at the wheel of corporate reputation management: companies’ performance in this area relates to their ability to earn a license-to-operate by stakeholders such as regulators and policy makers. For CEOs, this means that a clear focus on responsibility and accountability is the way towards reputational gains. For communications executives, there is a growing need to reframe corporate narratives and reconsider the way companies can earn stakeholders’ trust.

For more on this topic, read our analysis Crisis PR After a Hack: Case Studies.