We previously used Commetric’s Media Analytics to identify and discuss the companies at the centre of the media conversation around consumer boycotts. In this article, we will be taking a closer look at how boycotts spread on social media, with a specific focus on the role of Twitter.

Twitter is the breeding ground for consumer activism. As the focal point for political and cultural discussion online, it is not surprising that campaigns such as #MeToo and #GrabYourWallet which started on the platform have become global movements.

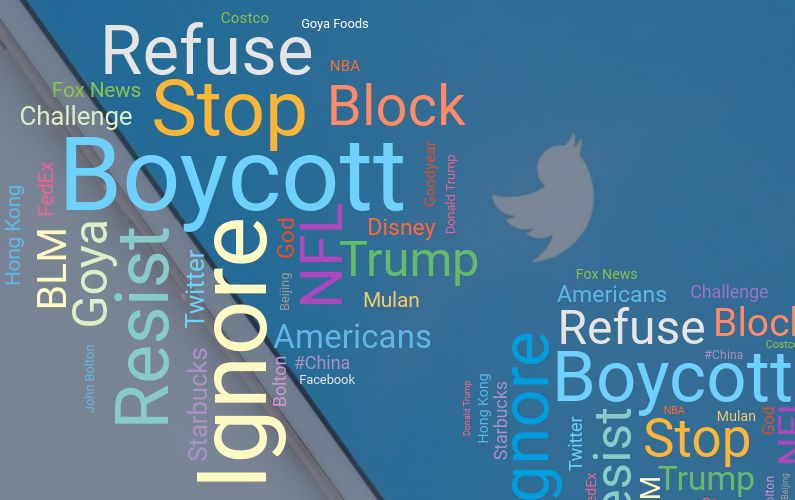

We decided to explore the Twitter conversation around consumer boycotts, analysing 1.91 million English-language tweets by US and UK users who called for boycotting something between January and September 2020.

The table below shows the trend of boycotts on Twitter over this period, and highlights the campaigns that gained the greatest traction.

The most significant peak was on 30 March, when the #BoycottTrumpPressConferences movement took off, with Trump’s critics deciding to boycott his briefings about the coronavirus. Many users felt that the President is using the briefings as personal campaign rallies, attacking reporters and other politicians.

The other significant peak was on 10 July with #BoycottGoya, which managed to create quite the Twitter storm. There were some smaller peaks in between, for instance on 4 February with #BoycottSOTU, where users supported the boycott of Trump’s State of the Union Address, initiated by some Democratic members of Congress.

Another minor peak happened on 12 June with #BoycottStabucks, with users protesting against the coffee giant’s decision to prohibit its workers from wearing accessories or clothing mentioning the Black Lives Matter movement. Although Starbucks cited its dress-code policy that targets anything to do with politics or religion, many users found that inconsistent given that it entered the Black Lives Matter conversation on social media by tweeting its support for the movement. Some users even pointed out that Starbucks’ logo came from the black goddess Yemaya.

But the most often used hashtag was #BoycottChina, which was sometimes used together with hashtags such as #BoycottMadeInChina and #BoycottChineseProducts.

The hashtag was posted for various reasons, with users expressing their opinions about issues such as police brutality in Hong Kong, privacy concerns related to Huawei or TikTok, forced labour, food quality and so on.

#BoycottChina was also boosted by more specific campaigns: for example, India’s largest conglomerate company JSW Group decided to cut down imports from China worth USD 400 million to ‘zero’ following the deaths of 20 Indian soldiers at the contentious Indo-Chinese border in June – an event which sparked ongoing protests in India.

Many users also blamed China for the coronavirus pandemic, using additional hashtags like #ChinaVirus, #MakeChinaPay and #ChinaLiedPeopleDied and tweeting that they refuse to buy “Made in China” products from big brands like Burberry or Nike.

There were also users pushing the popular conspiracy claim suggested the coronavirus was some kind of a biological weapon most probably developed by the Chinese government – a rumour which appeared shortly after the virus struck China. Many social media accounts propagating the theory cited two widely-shared articles claiming that the coronavirus is part of China’s “covert biological weapons programme”. They were published by The Washington Times, an outlet infamous for rejecting the scientific consensus of climate change and for promoting Islamophobia.

Twitter has been a significant vector for misinformation around the virus, but the social media giant has started to promote reliable medical information more heavily: the platform is prioritising countries’ health authorities in the search results, and users searching for “coronavirus” or “Wuhan” on the platform now see a message telling them to “know the facts”.

For more on this topic, read our analysis “Coronavirus Infodemic: Can We Quarantine Fake News?”

O tempora, o mores

Meanwhile, the NFL, a league in which the majority of players are black and the audience is mostly white also found itself threatened by player activism. The calls for boycott were provoked by issues relating to kneeling during the national anthem: after NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell admitted the league was wrong to discourage players from protesting in this way, many users were angry with the league for abandoning the argument that kneeling disrespects the flag.

Tire manufacturing company Goodyear was caught up in another Trump-related row after a photo allegedly taken at a Kansas Goodyear diversity training went viral. The photo indicated that while it was permitted to wear clothing with slogans supporting LGBTQ rights or the Black Lives Matter movement, clothing with slogans such as “All Lives Matter” or MAGA was not allowed. Naturally, Trump called for a boycott of the company, while right-wing media outlets were outraged.

Retail company Costco‘s case was also an interesting one – after it announced that shoppers will be required to wear face coverings in stores, angry consumers called for a boycott, saying that masks are not proven to help prevent the spread of the virus.

However, a tweet calling for the boycott of Disney film Mulan, posted by Hong Kong student activist and politician Joshua Wong Chi-fung, received the largest number of retweets in the conversation.

Mulan has divided critics and Twitter users to such an extent that members of Congress sent a letter to Disney demanding answers. The calls for boycott revolved around two Chinese issues: the treatment of Uyghur Muslims in China’s Xinjiang region, where parts of the film were shot, and China’s attitude towards Hong Kong.

All the China-related rows made the word “Chinese” the top entity in the Twitter conversation.

Juxtaposing our social media analysis with our traditional media analysis, we find that although there are obvious differences in priorities (Amazon and Apple’s troubles were well-covered by media outlets, but didn’t generate much excitement on Twitter), one thing kindles the interest of both journalists and Twitter users – China.

China has proven to be one of the most divisive issues in the US in 2020, generating a lot of anger on Twitter – the emotion that spreads faster and farther on social media than any other, as per a study conducted by Beihang University.

The spread of anger often results in outrage cascades — outbursts of moral judgment which start to drive the conversation around brands, their products and their corporate messages. The virality of moral judgements is facilitated by the fact that most of the content on social media feeds and timelines is sorted according to its likelihood to generate engagement.

This aligns with another research that found nearly 2 in 3 consumers are now belief-driven buyers – a trend which is now mainstream around the world, spanning different generations and income levels. A brand’s stand is one of the main drivers of interest, as many consumers express purchase intent or intent to advocate for the brand after viewing a product or brand communication relating to the brand’s stand.

The importance of boycotts

Because they don’t have an immediate impact on earnings, and sales declines have a statistically insignificant bearing on whether a boycott was successful, many C-level professionals are inclined to think that boycott movements are mere fads. But this type of consumer activism is vitally important for one particular department: public relations. As numerous studies have found, the real power of a boycott lies in its ability to hurt corporate reputation by generating negative media coverage.

Empirical analysis demonstrates that protests are more influential when generating greater media coverage: a study of 133 corporate boycotts conducted by Northwestern University’s Kellogg School of Management found that media coverage of boycotts is detrimental to a company’s reputation and that the stock price of a targeted company dropped by nearly 1% for each day it got national media coverage. Perhaps more importantly, about 25% of boycotts that received national media attention resulted in concessions from the targeted company.

Understanding the ways these boycotts spread is therefore imperative to protecting your company’s reputation and financial security.

As we saw, the Twitter discussion consists of peaks of passionate calls for a boycott of something that are soon replaced by calls of boycotts of something else, just as #BoycottStarbucks was swiftly replaced by #BoycottGoya. However, what’s important for PR professionals is to study the mechanics of these movements in order to design a good boycott response strategy.

As the most severe social media crises happen because of outrage cascades, PR professionals should carefully approach topics that are typically polarising. At the start of each campaign, PR execs should be asking themselves questions like: “Is my campaign touching upon a socially sensitive issue? If so, is the company’s overall messaging and actions in line with that position?” Consistency is key – remember how Starbucks faced calls for a boycott because its actions were at odds with its position on a sensitive issue.

Even if their firms aren’t the target of a boycott, PR practitioners should regularly monitor traditional and social media to be aware of the latest political and social issues that might trigger consumers.

Scoping the broad marketing environment (demographic, economic, cultural, natural, technological) could serve as the basis for identifying potential activism threats. It’s vital to understand the drivers of boycott calls in order to take appropriate countermeasures.

Firms should therefore pay close attention not only to calls that gain broad media coverage but also to the small blips on the social media radar that have the potential to gain traction. The volume of public backlash could start gaining momentum like a boulder down a mountain, leading to serious reputational hazards for a brand and for a whole industry.