- Although the concept of biodiversity is not that popular in comparison to climate change, an increasing number of scientists and activists are making the case that the two issues are closely linked and need to be tackled together.

- Our analysis found that the media debate around biodiversity has focused on countries such as Brazil, China and Indonesia, while NGOs such as Greenpeace and WWF set the tone of the conversation through activism and research findings.

- We suggest that comms professionals aiming to put biodiversity higher on the global agenda should evoke emotions to complement the science, highlight the link with climate and include people in the biodiversity concept.

View a one-page infographic summary of the analysis.

Biodiversity loss has been eclipsed by climate change on the global agenda and in the mass media. According to some commentators, climate has simply gotten more attention because it generates more media headlines as people are increasingly feeling it in their own lives – whether it’s wildfires or hurricane risk. However, more and more specialists have started to promote the idea that the two issues are closely linked, have similar impacts on human welfare and need to be tackled urgently, together.

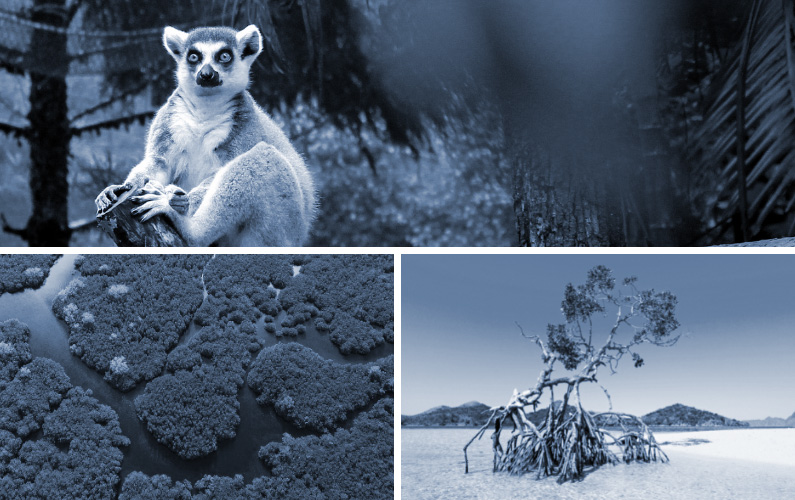

For example, the destruction of forests and other ecosystems undermines nature’s ability to regulate greenhouse gases in the atmosphere and protect against extreme weather impacts – accelerating climate change and increasing vulnerability to it. The rapid vanishing of carbon-trapping mangroves and seagrasses both prevents carbon storage and exposes coastlines to storm surges and erosion.

The extinction rate of species is now thought to be about 1,000 times higher than before humans dominated the planet, which may be even faster than the losses after a giant meteorite wiped out the dinosaurs 65m years ago. The sixth mass extinction in geological history has already begun, according to some scientists.

Growing awareness of these problems led an increasing number of scientists to call for governments to enact policies and nature-based solutions to address both issues. Meanwhile, environmental activists urged countries to protect entire ecosystems rather than iconic locations or species, claiming that policymakers tended to see climate change and biodiversity loss as separate issues, which resulted in policy responses being siloed.

And despite the coronavirus pandemic and the many lockdowns, 2021 saw the world’s scientists, volunteers and conservationists continuing their efforts to protect nature. The International Union for Conservation of Nature launched its new green list of protected and conserved areas, researchers at the Natural History Museum worked on digitising its vast collection, Kenya held its first animal census, and a multimillion-pound project was launched that aims to describe and identify the web of life in large freshwater ecosystems with “game-changing” DNA technology.

Biodiversity as a nation branding concern

Analysing 2,743 English-language articles published in top-tier outlets between March 2020 – March 2022, we found that the biodiversity debate centred around specific countries where preserving biodiversity has been a particular problem.

Our analysis showed that Brazil was in focus during the last two years:

Brazil has been prominent mainly because of all the news about the Amazon rainforest, the world’s largest tropical rainforest, famed for its biodiversity. Recently, Brazil made many headlines when a report by its space research agency Inpe found that deforestation in the Amazon rainforest has hit its highest level in over 15 years. According to the latest data, some 13,235 sq km (5110 sq miles) was lost during the 2020-21 period, the highest amount since 2006.

Many journalists painted the country in a negative light, pointing out that the Amazon is home to about three million species of plants and animals, and one million indigenous people, and is a vital carbon store that slows down the pace of global warming. Brazil was among a number of nations that promised to end and reverse deforestation by 2030 during the COP26 climate summit.

China followed Brazil in terms of media influence as it launched a new nature protection fund, trying to become a champion of biodiversity. Chinese President Xi Jinping announced the launch of a 1.5 billion yuan ($232.47 million) fund to support biodiversity protection efforts in developing countries. China also announced that it has upgraded the protection of 65 species of wild animals to the highest level. The move means that these endangered species, such as jackal and the Yangtze finless porpoise, will be under the strictest protection.

Meanwhile, China, the European Union and Japan were among countries pledging to spend more on slowing down rapid species loss. Apart from the 1.5 billion yuan pledged by Xi Jinping, the European Union also said it would double funding for biodiversity. France and Britain also promised to direct more of their climate budgets to protect biodiversity, and Japan announced a $17 million extension to its own biodiversity fund.

Indonesia came third as it is the world’s largest producer of palm oil, a versatile edible oil found in consumer goods from food to cosmetics. It is also home to the biggest forests outside of the Amazon and Congo. Environmental groups have blamed palm oil cultivation for widespread deforestation and the killing of endangered animals.

Norway was in the spotlight as six environmental organisations, including the World Wildlife Fund and Greenpeace, called on it to stop plans to open ocean areas for deep-sea mining. They also called on Norway to speak up against deep-sea mining in international waters at the International Seabed Authority (ISA), a Jamaica-based UN body that discusses rules for seabed mineral production.

Norway also joined the United States, the United Kingdom, and a group of companies including Amazon to launch a $1 billion initiative to protect tropical forests as part of a wider effort to lower greenhouse gas emissions by 2030. The three governments unveiled the Lowering Emissions by Accelerating Forest finance coalition to focus on reducing emissions from tropical and subtropical forest countries as well as ending deforestation. The announcement comes after President Joe Biden set an ambitious target of reducing emissions roughly in half by 2030 at a virtual climate summit as Washington looks to take on a leading role in the global effort to tackle climate change.

Biodiversity, alongside sustainability more generally, is becoming a major nation branding issue. As we in our analysis of the Dubai Expo, countries which framed themselves as sustainability hubs managed to gain substantial media attention – many countries’ pavilions across the Expo site aimed to highlight their pioneering efforts to battle overconsumption, overproduction and sustainable management of resources.

NGO-dominated discussion

We used Commetric’s proprietary ‘media conversation impact score‘ metric to identify the organisations with the biggest impact on the media discussion around biodiversity.

We determine an organisation’s media impact in the context of a topic by looking at its media influence score calculated in terms of coverage by high-profile media outlets, topic relevancy score measuring its contextual relevance, and media visibility as measured by the number of mentions.

We found that the debate was dominated by NGOs and environmental groups, many of which gain media visibility as they call for nations to boost spending on biodiversity conservation.

Greenpeace, known for its direct actions and has been described as one of the most visible environmental organisations in the world, emerged as the most influential organisation as journalists either mentioned its research findings or covered its campaigning efforts.

For example, Greenpeace featured in many reports around Brazil as it found that one-third of deforestation in the Amazon is linked to so-called land grabbing of public land, mainly driven by meat producers clearing space for cattle ranches.

And in April 2021, Greenpeace made headlines as it protested against deep-sea mining in the Pacific, with the environmental organisation’s Rainbow Warrior boat trailing a ship doing research for Deep Green, a company that plans to mine the seabed for battery metals. “The deep ocean is one of Earth’s least understood and least explored ecosystems, which is home to significant biodiversity, and also acts as a vital carbon sink,” Greenpeace said in a statement, adding that mining the deep sea is not needed to power the energy transition, especially if governments commit to resource efficiency and a circular economy.

Wildlife charity The World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) was the second most influential organisation in our sample as it claimed that forests across the world which together cover an area nearly twice the size of the UK were destroyed in just 13 years. It found that 43 million hectares (166,000 square miles) of forests and habitat in those areas had been destroyed between 2004 and 2017, leaving large areas of remaining forests and the wildlife that live in them under threat.

WWF also received media attention for work within specific countries – for example, it found that Canadian wildlife at risk of extinction has undergone “staggering” losses over the past 50 years. In addition, the organisation called on African governments to invest in nature to help spur green economic recovery for post-COVID-19, saying that Africa can build a more resilient and sustainable future centred on healthy people and a healthy planet.

In the meantime, the U.S.-based World Resources Institute (WRI) developed a new online platform that aims to connect people who can plant trees with investors with millions of dollars to spend in a bid to stem deforestation worldwide. Big businesses and governments have pledged to plant trees and invest more in forest conservation in recent years, but connecting them with non-profits and local farming cooperatives who plant trees in countries with swathes of tropical forests has been difficult, WRI said.

Biodiversity as a corporate priority

Some large companies managed to gain positive media coverage for promoting their biodiversity efforts. For example, Google, BMW, Volvo and Samsung were the first global companies to sign up to a WWF call for a moratorium on deep-sea mining, likely shrinking the potential market for deep-sea minerals harvested for our cars and smartphones. The move away from fossil fuels to electrify the global economy is creating an ever-increasing demand for the materials that go into batteries, some of which are found on the seabed whose ecosystems have yet to be fully explored.

In backing the call, the companies committed not to source any minerals from the seabed, to exclude such minerals from their supply chains, and not to finance deep seabed mining activities. Deep-sea mining would extract cobalt, copper, nickel, and manganese – key materials in batteries – from potato-sized nodules that pepper the seafloor at depths of 4-6 kilometres and are particularly abundant in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone in the North Pacific Ocean, an area spanning millions of kilometres between Hawaii and Mexico.

BMW said raw materials from deep-sea mining are “not an option” for the company at present because there are insufficient scientific findings to be able to assess the environmental risks, while Samsung said it was the first battery maker to participate in WWF’s initiative.

However, Google еmerged as the most influential company as a number of journalists mentioned Wildlife Insights, an initiative of Google Earth Outreach’s Nature Conservation program, which was announced to help conservation experts as well as local communities reduce the time-consuming manual tasks of processing and analysing images—while sharing knowledge with researchers around the world, and protecting species from extinction.

But others weren’t covered in such a positive light – for instance, Cargill, the US-based commodity giant, and agriculture trader Bunge have been linked to deforestation. Recently, France has named Cargill and Bunge as the leading importers of soybeans from areas at risk of deforestation. The companies have been identified as the French government tries to clean up the country’s agriculture supply chains with the launch of an online database that tracks soybean exports from Brazil to France. The database showed about a quarter of Brazilian exports of soybeans to France in 2018 came from areas hit by deforestation.

Bunge said it was committed to reaching deforestation-free supply chains by 2025 and had already removed some farmers linked to deforested land from its supply chain. Cargill claimed the platform’s data did not reflect French imports, adding that it was committed to eliminating deforestation in the shortest time possible, but that there was no single solution to the issue.

Nestlé, the world’s biggest food company, gained media attention as it made significant progress removing cocoa produced in protected forests in West Africa from its supply chain as pressure builds from consumers and governments for ethically sourced cocoa. The company said it had mapped, using GPS coordinates, 75% of the 120,000 cocoa farms it sources from directly in Ivory Coast and Ghana, which produce some two-thirds of the world’s cocoa. It found around 3,700 farms in protected forests in the process of mapping and removed them from its supply chain.

Unilever took similar steps, using a combination of advanced satellite imagery and geolocation data to help it understand exactly where some of its raw materials come from for its products, which range from Ben & Jerry’s ice cream to Axe deodorant. It has historically been hard for the firm and other multinationals to trace the exact origins of those ingredients down to the individual farm or field, according to Marc Engel, the company’s chief supply chain officer.

BlackRock was the most influential financial services giant, as it warned companies that rely on nature or have an impact on natural habitats to publish a “no deforestation” policy and their strategy on biodiversity or face pushback from the asset manager at their annual meetings. The world’s biggest asset manager is keen to position itself as a leader in sustainable finance and over the last year has looked to take a tougher position on companies not performing on environmental, social and governance-related issues.

Biodiverse spokespeople

The media’s focus on Brazil made Hamilton Mourao, who is leading the Brazilian government’s Amazon protection efforts, the most influential spokesperson in the debate:

Amid growing criticism of Brazil’s environmental policy from environmental groups as well as international investors, Hamilton Mourao was quoted as saying that Brazil plans to bring forward its 2030 goal of ending illegal deforestation by two or three years. Mourao said forest fires in the Amazon region had dropped significantly, by about 40% this year. And when Environment Minister Ricardo Salles said it would cease fighting deforestation due to a lack of funds, Mourão quickly denied the statement saying “that’s not going to happen.”

Meanwhile, Marcio Astrini, head of the environmental advocacy group Climate Observatory, argued that rising deforestation is proof that Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro‘s recent promises to protect the Amazon should not be taken seriously. “Brazil has achieved the feat of being perhaps the only large emitter that polluted more during the first year of the pandemic,” he said.

Amidst the triple environmental threat of biodiversity loss, climate disruption and escalating pollution, United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres launched “an unprecedented effort to heal the Earth,” on the eve of World Environment Day in June. Kicking off the UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration, the UN chief said the planet was rapidly reaching a “point of no return,” cutting down forests, polluting rivers and oceans, and ploughing grasslands “into oblivion.”

His colleague Inger Andersen, executive director of the United Nations Environment Programme, was cited as saying that since 2009, we have lost more coral, worldwide, than all the living coral in Australia: “We are running out of time: we can reverse losses, but we have to act now.”

The most influential academic in the discussion was Partha Dasgupta, professor of economics at the University of Cambridge, who stated that economics hasn’t done a good job of pricing in the impact of human activities of nature. The professor regards nature as the most precious asset of all human beings, and he said that more effective measures should be taken to protect the environment before things get worse.

As with many nature-related discussions, Sir David Attenborough was also widely quoted as saying the excesses of western countries should be curbed to restore the natural world and we’ll all be happier for it. The veteran broadcaster said that the standard of living in wealthy nations is going to have to take a pause. Nature would flourish once again he believes when “those that have a great deal, perhaps, have a little less”.

The most prominent corporate spokesperson was former Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos, who gave $1 bn to efforts around biodiversity. Bezos, who recently made headlines by flying in a spacecraft built by his rocket company, Blue Origin, called the loss of Earth’s forests a profound and urgent danger to us all: “I was told that seeing the Earth from space changes the lens through which you view the world,” he said. “But I was not prepared for just how much that was true.”

How can comms put biodiversity higher on the global agenda?

Whether working for governments, NGOs or multinational companies, biodiversity communicators across the world face the same challenge – to translate complex science into compelling messages that will inspire the action required to conserve biodiversity.

Here are a few suggestions how this could be achieved, based on our analysis:

- Evoke emotions to complement the science. Biodiversity science provides the foundations of our understanding and is an essential provision for policy making. However, it rarely succeeds in inspiring public action on its own. In part, this is because it is a complex topic, and is simply hard to understand for many people. It also comes down to human nature. Most people are not rational and don’t make daily decisions based on logical scientific analysis. Instead, they are motivated by a mixture of emotion, habit and social norms. It is how biodiversity makes them feel, not think, that leads them to act. Biodiversity is the world’s most elaborate scientific concept, but also, potentially, its greatest story. Love of nature for most people is about awe, wonder and joy; not habitats, ecosystem services or extinction.

- Highlight the link between the climate and biodiversity crises. While climate change has been all around the media in the last few years, biodiversity is yet to emerge as an issue of concern. However, PR pros should clearly demonstrate the link between the climate and biodiversity crises, and speak of biodiversity with the same tone of concern. In this way, the general public could understand that climate change is not only greenhouse gases and ozone. Many media stories in outlets like the Guardian have already underlined the connection between these issues, often focusing on specific problems – for example, bats sweltering in their boxes, polar bears and narwhals using up to four times as much energy to survive, birds starving as Turkey’s lakes dry up, and unique island species at high risk of extinction as the planet warms.

- Include people in the biodiversity concept. Biodiversity could become a clearer issue if the concept includes not only forests and species but human beings as well. This could help the general public feel that it’s part of the global ecosystem rather than treat it like an external problem that needs to be solved. Comms professionals can’t hope to tackle climate change without also addressing the structural inequities that mean some groups – such as women, BIPOC communities, LGBTQ+ communities and people with disabilities – are disproportionately impacted. PR pros need to address the social dimension of global warming, showing that they understand that the most vulnerable people bear the brunt of climate change impacts yet contribute the least to the crisis. As the impacts of climate change mount, millions of vulnerable people face greater challenges in terms of extreme events, health effects, food security, livelihood security, water security, and cultural identity.

- Go beyond preserving nature and focus on regeneration. Regeneration is all about a positive impact rather than just doing less harm to the planet. A truly regenerative approach will be properly yoked to comms and branding initiatives from strategy to social justice, guiding decision-making and delivering positive impact across the triple bottom line of people, planet and prosperity. According to a Wunderman Thompson study, 83% of consumers think businesses and brands should focus on a positive impact, rather than just doing less harm to the planet. A more specific action rather than making just a pledge also goes a long way. Take BrewDog, which claims to be the world’s first carbon-negative brewery. It has purchased land in Scotland to create a BrewDog Forest of 1 million trees and restored peatland. In so doing, the brand is carving a reputation as a leader tackling the climate crisis.

Learn more about how Commetric’s Media Analytics can supercharge your communications strategy with the essential insights necessary to boost your reputation.