The business media is full of expressions such as “every company is a… [fill in the blank] company”. The most popular example is “every company is a technology company”, which is often modified to “every business is a digital business” and, if we want to sound really cutting-edge, “every industry is an internet of things (IoT) industry.” Such clichés aim to emphasise that in every sector, from finance to healthcare, the technology which powers a company has become just as important to that company’s prosperity as the quality of the products or services it offers.

One of the main consequences of this technological ubiquity has been the overabundance of data and information. As a result, conveying corporate messages in the right way is becoming more and more challenging in our increasingly hyper-connected engagement-driven economy. This has brought forward another oft-cited phraseological unit – “Every company is a marketing/media/PR company” – which goes to show that in every sector, the reputation a company enjoys has become just as essential to that company’s prosperity as its products or services.

At a time when one-way, “push” advertising is losing its relevance, companies see the need to become effective marketing vehicles. As McKinsey puts it: “At the end of the day, customers no longer separate marketing from the product—it is the product. They don’t separate marketing from their in-store or online experience—it is the experience. In the era of engagement, marketing is the company.”

The study of reputation: a philosophical perspective

Researchers generally agree that a company’s market value can hardly be derived from tangible assets but is rather determined by its central intangible asset: its reputation. Regression analyses using reputation and stock data have demonstrated that a long-term engagement in reputation-building activities has a positive impact on the shareholder value (Schwaiger 2011).

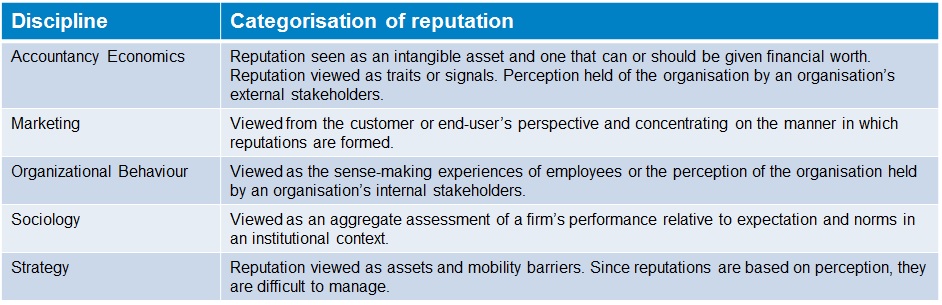

And while no one would deny that corporate reputation is of utmost importance, there is no general consensus about what “reputation” actually means. In their search for definitions, academics have used the analogies of ‘Scaling the Tower of Babel’ (Hatch and Schultz 2000, 11) and ‘fog’ (Balmer 2001). Fombrun and van Riel (1997) have provided a practical guide from the perspective of six subject areas:

Source: Fombrun and van Riel (1997).

If we are to employ such an inter-disciplinary approach, reputation should also be considered from the perspective of its core discipline – epistemology, the study of knowledge and its acquisition. This philosophical field has recently been divided into two subcategories: individual epistemology and social epistemology. The former and more traditional one looks into private doxastic attitudes, while the latter strives to investigate social interactions, and the public and institutional aspects of acquiring and transmitting information.

Contemporary social epistemology is developed within a “veritistic” framework, as an opposition to the so-called “debunking” thinkers who tried to challenge the objectivity of truth and facts, dismissing them as something “constructed” in social discourse. Such ambitions to undermine the traditional epistemological and metaphysical notions of truth and facts are most commonly associated with postmodernist thinkers and members of the “Strong Programme” in the so-called sociology of science, whose examination of social practices endorsed relativistic attitudes.

In contrast, analytic philosophers (Goldman 1978: 509–510; 1986: 1, 5–6, 136–138; 1987) have taken an objectivist approach aligned with traditional epistemology, which investigates the way social practices influence the acquisition of knowledge. The first serious exploration of this initiative was Alvin Goldman’s book “Knowledge in a Social World” (1999), whose main idea is that the “rigour” of traditional epistemology could be transferred to the epistemic investigation of social practices (Goldman and Blanchard 2018).

The aim of veritistic social epistemology is to “evaluate social practices in terms of their veritistic outputs, where veritistic outputs include states like knowledge, error and ignorance” (Goldman 1999: 87), and to study social practices “with regard to their impact on knowledge acquisition” (Fallis 2000: 305).

The main way of acquiring knowledge from social practices is our everyday media consumption: from newspapers to online media outlets, social media, search engines, blogs, online encyclopedias, video platforms, and so on – platforms which bang out more and more information on a daily basis.

The overabundance of information leads to what Italian philosopher Gloria Origgi (2018) calls “an underappreciated paradox of knowledge”: the access to so much information does not empower us or make us more cognitively autonomous but makes us more dependent on someone else’s judgments and evaluations. Thus we are experiencing a fundamental paradigm shift in our relationship to knowledge, according to Origgi: “From the ‘information age’, we are moving towards the ‘reputation age’, in which information will have value only if it is already filtered, evaluated and commented upon by others. Seen in this light, reputation has become a central pillar of collective intelligence today.”

This means that epistemic sources – the channels transmitting knowledge – are becoming increasingly important. In the context of social epistemology, the most wide-spread sources are journalists, spokespeople, experts, academics, industry professionals and so on – people whom we call key opinion leaders and who are an essential part of every media discussion.

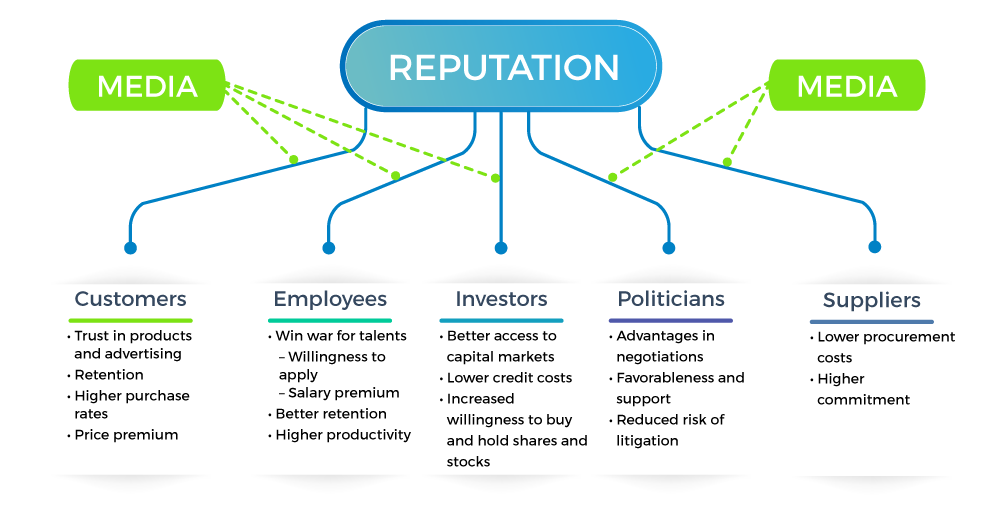

The more information we have access to, the more we rely on reputational devices to assess it. In the case of corporate reputation, our knowledge of a certain company depends on what we’ve gathered from our epistemic sources. The following graph by Schweiger (2011) illustrates the role the media plays in this process:

Building reputational paths

The primary goal of a mature citizen, according to Origgi, should not be examining new information per se but reconstructing the reputational path of that information, asking questions such as: “Where does it come from? Does the source have a good reputation? Who are the authorities who believe it? What are my reasons for deferring to these authorities?”

Asking such questions would be far more practical than investigating the reliability of the information ourselves. For instance, when we lack the competence and the time to research the eventual correlation between vaccines and autism ourselves, we should focus on the social network of relations that has made certain data available to the public.

In epistemology, the process of acquiring knowledge from trusted sources is often dubbed “learning from the testimony of experts”. In contemporary social sciences, the term “experts” in this context is substituted by “key opinion leaders” or “influencers”.

In media studies, this process is described by the two-step flow of communication model, introduced by Paul Lazarsfeld, Bernard Berelson, and Hazel Gaudet in a 1944 research of the process of decision-making during an election campaign. Initially, the researchers anticipated empirical proof for the immediate influence of media messages but instead found out that individuals (opinion leaders) were the primary sources of influence.

In the two-step flow of communication theory, which is the basis of contemporary influencer marketing, opinion leaders convey their own interpretations of the actual media messages. This mediation between the media’s messages and the way the audience receives these messages is often described by the term ‘personal influence’ to underline the impact opinion leaders have on the public’s attitudes and behaviours. This aligns with Origgi’s idea that in our reputation age, information has value only if it is already filtered, evaluated and commented upon by others.

Paletz, D.; Owen, D.; Cook, T. 21 century American Government and Politics, Chapter 7, adapted from Katz, E., Lazarsfeld, P. Personal influence (New York: The Free Press, 1995). Source: Media Studies 101, A Creative Commons Textbook

We can provide an empirical example from a research of the media discussion around Alzheimer’s that we recently conducted using our Influencer Network Analysis (INA) methodology, which employs natural language processing, entity extraction, free-text data mining and dynamic network mapping technology, complemented by human-led analysis. Analysing the diffusion patterns and conversation flow, we found out that the articles featuring influencers’ opinions are the ones top trending on social media, and that opinion leaders make stories diffuse farther and deeper.

For instance, many media outlets reported that Eisai, together with Biogen, developed a new drug treating mild Alzheimer’s dementia. But the reports which were most widely shared were the ones featuring expert commentary by people whom we had identified as opinion leaders in the context of Alzheimer’s. The article which got the highest number of Facebook engagements (1.3K) and Twitter shares (233) was a piece on Forbes, which included comments by Sam Gandy, a neurology professor at Mount Sinai Medical Center, and by Lon Schneider, a doctor and Alzheimer’s researcher at the University of Southern California.

The second most popular article on the same subject was on CNBC and featured the opinion of Maria Carrillo, chief science officer at the Alzheimer’s Association, while the third was on Vox and was enriched with comments by Keith Fargo, director of scientific programs & outreach at the Alzheimer’s Association, and Ronald Petersen, director of the Mayo Clinic Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center.

The conclusion from our case study was that if pharma players want to dip their toes into challenging markets like Alzheimer’s, they would need to draft an effective influencer-based marketing campaign. For more pharma insights, read our blog post “PR Measurement in Pharma: The Key to Effective Communication Strategies“.

Given the paradigm shift in our relationship to knowledge, a company can build its brand by carefully designing specific reputational paths. Following the two-step flow of communication model, this means employing opinion leaders who would serve as the audience’s epistemic sources and move the media conversation forward in an efficient way. The first step towards such outreach programmes is identifying the key influencers and their relationships to particular topics. This can help organisations engage with new audeinces beyond their usual outreach.

For example, in our award-winning work with the International Diabetes Federation (IDF), we explored the media discussion surrounding nutrition, sugar and obesity, highlighting potential partners for advocacy collaboration. We found the most prominent influencers and illustrated how they are interlinked, which allowed the IDF to become more targeted and efficient in its stakeholder outreach and overall communication strategy.

As a result, the IDF managed to build strategic alliances and partnerships beyond the diabetes landscape and forge new partnerships. As part of IDF’s G7 “Call to Action” campaign, the influencers made diabetes the second most mentioned topic on Twitter in connection with the G7, although that topic was not on the agenda.

Another way of designing reliable reputational paths is by making the company itself an opinion leader. This can be achieved by positioning corporate spokespeople as authorities who filter, evaluate and comment upon new information in their respective fields. Influencer mapping can identify the white space in a media conversation which can provide an opportunity for effective thought leadership strategies.

For instance, we recently found that the media conversation about various mental issues is becoming livelier, but it’s driven by public figures and celebrities, with pharma companies lagging behind. Some of the main topics are depression, anxiety and panic disorders, but there are no established pharma influencers speaking on these issues. The increasing liveliness of the debate creates excellent conditions for new commentators to bring in some fresh insights, and communication professionals in pharma could position their firms as thought leaders by examining the manner in which the conversation is currently carried on.

The importance of such processes was highlighted by the 2019 Edelman-LinkedIn B2B Thought Leadership Impact Study, which found that B2B buyers are likely to pay more to work with companies who have clearly articulated their vision through thought leadership.

Do you want to learn more about identifying key opinion leaders through Influencer Network Analysis?

Download the 12-page white paper by Commetric and learn how Influencer Network Analysis can be used to identify and rank the KOLs that drive media coverage on Alzheimer’s disease, and the related topics that generate traction with media outlets and reporters.